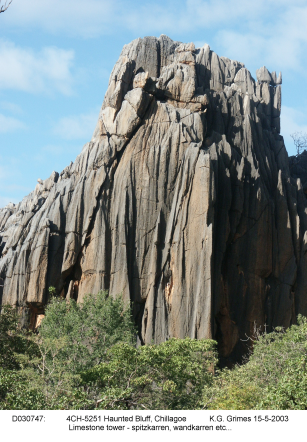

Showing spitzkarren, wandkaren etc...

File: D030747.jpg

The following text is an extract from the current draft of my chapter on Tropical Monsoon Karren in Australia for the "Karren Book".

The Chillagoe area is one of the better documented of the tropical karren in Australia (e.g Lundberg, 1976 (thesis), Ford, 1978, Pearson, 1982, Jennings, 1982, and Dunkerley, 1983). The area is best known for its serrated limestone towers (Figure ZA) which can reach up to 90 m high, though most are less than 50 m, and are from 100 m to over a kilometre long. Some are surrounded by a limestone pediment or alluvium, but others rise immediately beside the (commonly faulted) contact with the surrounding volcanic or sedimentary rocks. The overall size and distribution of the towers are structurally controlled by the narrow lenses of steep-dipping limestone which alternate with insoluble rocks that are less resistant to erosion (Jennings, 1981, 1982). The Mitchell-Palmer karst is similar to Chillagoe, but more remote and has larger towers.

Within the towers, giant grikes up to 10 m wide and 30m deep connect to fissure-maze caves with numerous daylight holes. Both the grikes and the caves tend to have flat earth floors or rubble piles. In places the grikes open out into karst corridors or deep steep-walled dolines of both solutional and collapse origin. Solution dolines on the tower tops tend to be irregular forms with spitzkarren spires and internal drainage via grikefields. Some towers have stepped relief with risers and treads.

Jennings, (1981, 1982) discussed the pediments, which, along with climatic control of tower form, had been given considerable emphasis in earlier work. He noted that, in fact, the pediments constitute less than half the tower perimeters. However, they are still active in many places and have cut back the tower flanks, in some cases reducing the tower to a scatter of fragments & ruins . The lower "scree" slopes of the towers are partly bedrock with a thin cover and Jennings (1982) referred to these ramps as "Richer denudation slopes" (Photo B =near Railway bridge). Some towers have marginal depressions with active subsidence of the soil which are the result of aggressive water runoff from tower surface (Pearson, 1982).

The towers may be quite old. Robinson (1978), Jennings (1982), Webb (1996) and Gillieson et al (2003) all discuss the age of the karst, noting the presence of isolated outcrops of quartz sandstone both on the tower tops, and around their bases. These sandstones have been attributed to the late Jurassic to early Cretaceous Gilbert River Formation of the Carpentaria Basin and Robinson (1978, p.32) refers also to associated shales with Triassic plant material, though Jennings (1982, p.48) notes that the dips on these shales suggest either downfaulting or formation as doline fill. The conclusion is that the towers were already well formed at the time of their burial during the early Cretaceous transgression. Their present form, and detailed sculpturing, would have evolved subsequent to exhumation in the late Cretaceous and early Tertiary. The caves within the towers are also old as they show phreatic character even at elevations close to the present top of the towers, indicating that they were dissolved prior to the lowering of the surrounding surface to its present levels (Ford, 1978; Robinson, 1978, p.23).

Jennings (1982) summarised the lithological control as producing poorly developed karren on the coarse-grained 'sugarstones' and heterogeneous limestones, and a much wider range of well-developed karren on the fine-grained uniform limestones - 'sparite', 'fossil' or 'reef' limestone. He also noted that excessive fracturing inhibits those karren that result from water flow over large surface areas. The following draws mainly on Pearson (1982) and Jennings (1982).

The white, coarsely-crystalline, marbles have been recrystallised by thermal metamorphism adjacent to intrusive granitic bodies. Joints (and hence grikes) are less abundant. They form smoothly rounded domes with exfoliation sheets that occasionally are raised up to form A-tents. Some surfaces show a crazed pattern of fine cracks. Rillenkarren do occur on the marble, but are less well developed. Lundburg (1977 thesis) tabulates the differences in character between the rillenkarren on the 'sugarstone' and those on the 'sparite' limestones (see also summary in Jennings, 1982, p.25). The 'sugarstone' differed from the 'sparite' limestone in having pits and flutes that were narrower, shallower, more constant in form and less close-set and had more rounded ribs between them.

The finer-grained marbles have karren forms that are more similar to the 'sparite' limestone. However, the grain size of the marble can be quite variable over short distances, so the above distinctions need to be applied with some care. Dunkerley (1988) compared runoff water and kaminitza waters from rock surfaces on three lithological groups (coarse and fine-grained marble, and fine-textured fossil limestone) and found that the fossil limestone (41.9 ppm total hardness) and the fine-grained marble (41.3 ppm) were dissolving more rapidly than the coarse marble (34.1 ppm),. His detailed results have not yet been published.

On the more gentle slopes, which include steps and bevels (Ausgleichflächen), there are rain pits, localised rosettes of rillenkarren, runnels, and small (up to 30cm wide) pans (kamenitza). Wilson (1975) reported that flat solution pans are common on tops of the towers, and noted that these always have a outlet drain.

The rillenkarren, in particular, have been studied morphometrically by Lundberg (1976,1977), Ford?? (1978??), Jennings, 1982), Dunkerley (1983). Jennings (1982) measured rillenkarren lengths on the 'sparite' that averaged 95 - 100 cm at three sites, with a SD of 48. Dunkerley (1983) summarised the results in Lundberg's (1976) thesis, and also reported additional measurements giving flute lengths averaging between 17.3 and 29.8cm and widths of 16.9 to 18.5mm at three sites on the marble, whereas two 'sparite' sites had lengths of 31.3 & 35.6cm and widths of 18.5 & 23mm.

See also ...

The images are mostly large and you can zoom in to look at the detail.

|

A typical tower at Chillagoe - developed on the "sparite" or "reef" limestone. Showing spitzkarren, wandkaren etc... File: D030747.jpg |

|

The side of Dome Rock; developed on the "sugarstone" marble. Note the smooth sides, exfoliation flakes and solution hollows. File: D030690.jpg |

|

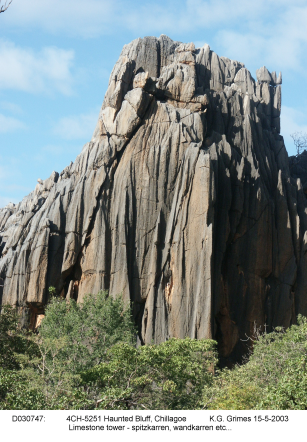

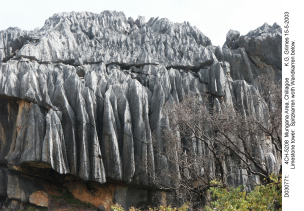

Top of a tower. Spitzkarren at top changes to vertical wall karren below. File: D030771.jpg |

|

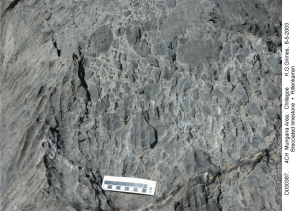

Rillenkarren on a steep face. A combination of rillenkarren and rundkarren form a type of spitzkarren ? File: D030383.jpg |

|

A combination of rillenkarren and rundkarren form a type of spitzkarren. File: D030384.jpg |

|

|

Spitzkarren with cockling. Stereo-pair - view cross-eyed. File: D030396.jpg and ..397 |

|

|

Rillenkarren and steps. Stereo-pair (exaggerated) - view cross-eyed. File: D030760.jpg and ..759 |

|

|

Spitzkarren, rillenkarren, "rain-pits" and steps. Stereo-pair - view cross-eyed. File: D030762.jpg and ..761 |

|

|

Runnels on top of a block. Stereo-pair - view cross-eyed. File: D030402.jpg and ..401 |

|

Solution step and flutes (rillenkarren) File: D030704.jpg |

|

Flutes with cockling. File: D030784.jpg |

|

|

Deep pitting (cockling?) on a vertical face. Stereo-pair (exaggerated) - view cross-eyed. File: D030773.jpg and ..772 |

|

Brecciated limestone + rillenkarren File: D030387.jpg |

(c) KG. Grimes, 2003