Background

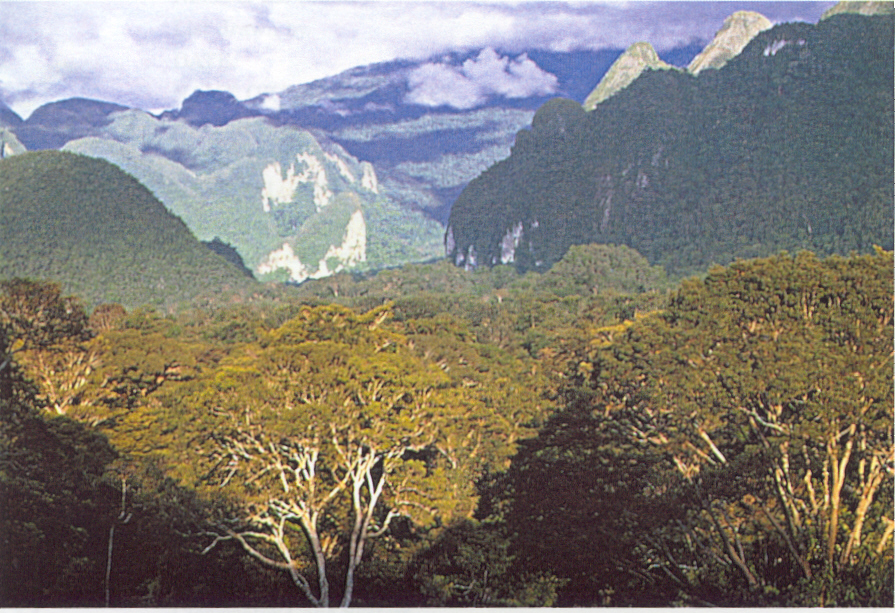

Although Malaysia ratified the 1972 UNESCO Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage in 1988, no nominations for either cultural or natural heritage were put forward. Profs Derek Ford and Paul Williams (1989) commented that the establishment of a series of karst world heritage sites is both justified and due. Gunung Mulu was specifically mentioned as of immense significance as a tropical karst ecosystem, both above and below ground.

Shortly after the 1994 Geomorphological Conference in Singapore I had the opportunity to conduct Paul, Derek and many of the worlds foremost karst geomorphologists on a tour of the park. At that time I was employed as development officer, a short time later to form and head the Karst Management Unit of the Sarawak Forest Department. All expressed the same opinion that the Gunung Mulu National Park was a sure fire candidate to complement other karst regions throughout the world on the world heritage list and others in the process of nomination.

I put forward a proposal to the Sarawak Forest Department for world heritage listing but this was turned down, as at that time the government had no intentions of nominating any sites. It was also thought that there could be foreign interference in the management and development of Sarawak parks that could be disadvantageous.

The integrity of the park

At this time after a series of wildlife surveys spread over a number of years, it was realised that Sarawak's wildlife was under considerable threat and work was started on The Sarawak Wildlife Master Plan (1996) in order to save it. On publication of the plan it became obvious that the amended 1993 National Parks and Wildlife Ordinance required urgent revision in order that the Wildlife Master Plan could be implemented.

I was assigned to the National Parks and Wildlife Committee, formed with the brief to compile a new National Parks and Nature Reserve Ordinance. The new Wildlife Protection Ordinance and the National Parks and Nature Reserve Ordinance came into being in 1998 and included a provision for "Concession Management" of park facilities.

Also provision was made for the setting up of "Special Park Committees" of local community leaders. This was in order to achieve local community participation in the management of parks and profit sharing schemes.

The new Ordinance was regarded as exemplary conservation law, the envy of many conservation workers in other countries. The integrity of Gunung Mulu was therefore adequately satisfied as regards to the conservation of its biodiversity, karst and caves and the involvement of the local community.

Privatisation proposals for the Gunung Mulu National Park were submitted by the Borsarmulu Resort Sdn Bhd, the holding company of the Royal Mulu Resort shortly after the publication of the new Ordinance. This tasteful resort built on the edge of the park boundary had expanded to 188 rooms, a massive investment, but was running at a loss due to the low tourist numbers. It was obvious that the Resort would be the prime candidate if privatisation were to be implemented. The Sarawak State Government put the matter on hold for the time being.

The World Heritage Nomination and Documentation

In 1998 it was noted by UNESCO that Malaysia was a blank spot on the world heritage map. This prompted Malaysia to host a Seminar on The Nomination of Cultural and Natural Heritage of Malaysia to the World Heritage List. I was asked to submit a brief proposal paper on behalf of the Sarawak Forest Department for the Gunung Mulu National Park, (Gill, 1998).

The Head of the Sarawak National Parks, Sapuan Hj Ahmad, presented the paper at the seminar in West Malaysia. A paper was also submitted by Ipoi Datan, the Deputy Director of the Sarawak State Museum for the Niah Caves, as a site of Cultural Heritage.

The Gunung Mulu proposal was evaluated by Peter Hitchock IUCN, who commented that Mulu would probably fulfill the criteria for nomination on the grounds of its great biodiversity, caves and karst, but that the management plan was out of date and required urgent review. Another comment made was on the great potential for a trans-boundary world heritage park with Brunei Darussalam.

Threats noted by the evaluator included the proposed Miri to Limbang road which would effectively sever the wilderness link with Brunei, impacting the integrity of the park; the need for replacement of infrastructure including inappropriate development of the caves; privatisation proposals beyond the leasing of buildings; the lack of professional staff; pollution to the caves from logging operations; the Royal Mulu Resort development and the relations with the local community.

A summary paper was prepared, (Gill, 1998) and the Sarawak State Government ratified the proposal for world heritage nomination for both Niah Caves and Gunung Mulu. The main Gunung Mulu documentation (Gill, 1999) was completed for the UNESCO dead line in June of 1999 after first being reviewed by Profs David Gillieson, Derek Ford and Elery Hamilton-Smith, to which the author extends his thanks.

I attempted to justify all four of the criteria for World Natural Heritage. Dr Jim Thorsell (IUCN) conducted an on-site assessment in January 2000. Jim was completely satisfied with the integrity and documentation for the park and seemed confident that Gunung Mulu would be listed at the Cairns UNESCO World Heritage Convention due to be held in Australia in December 2000.

At that time a new management plan was in the process of being compiled, the aim being to complete the draft in time for the December Convention.

The local community

The local community consists of "Orang Ulu" (interior people), both Berawan and Penan. The Penan were a nomadic tribe subsisting on hunting and gathering; the Berawans being settled, subsisted on rice cultivation, fishing and hunting.

The original inhabitants of the region were a group known as the Tring. It is documented that they farmed along the Melinau River and within the park over a long period. Over time the Tring intermarried with the Berawan, the main long house settlement being at Long Terawan on the Tutuh River.

The present long house on that site is situated one and a half hours by long boat from the park boundary. This is the third long house in living memory, the first having been burnt to the ground by the Japanese occupation forces in reprisal for guerrilla activities, the people losing all their possessions. Many of the old men of Long Terawan fought alongside the legendary late Tom Harrisson, although today the Japanese heads that adorned the long house are no longer to be seen. The last one belonged to my wife's late grandfather and the head, used for magic ceremonial purposes was disposed of in the river after his death.

The Perang responsible, still stained with congealed blood and hair, was passed on to one of my wife's uncle's and still resides at Mulu, waiting it is said to be used again if the need ever arose. Its renowned magical qualities though have long since disappeared with the death of its original owner.

In 1974 when the park was constituted only six families were known to farm near the park, mainly along the banks of the Melinau River. By 1985 when the park was officially opened for tourists, many more had built farmhouses and some construction began on tourist accommodation.

Logging activities in the region encouraged the nomadic Penan to settle at Batu Bungan, close to the park headquarters, on the Melinau River. Another group of Penan settled at Long Iman, just south of the park boundary on the Tutuh River.

Since 1985 the population has steadily increased now numbering over six hundred adults. Less than one hundred have any kind of steady income, the majority subsisting on farming, fishing, hunting, gathering and occasional laboring, boating or guiding work. Illegal activities within the park are therefore commonplace.

From 1985 until the opening of the Royal Mulu Resort in 1993, Berawan owned tour operators flourished but the local community were unable to compete with the luxury accommodation and services offered by the Resort. The decline was inevitable and by 1998 the majority of locally owned Tour Operators had been either taken over by outside operators or had gone into liquidation. It was therefore of great concern that the majority of the tour operators were owned, managed and employed people from outside the region. Also contracting work is predominately awarded to outside contractors. Contracts that could easily be awarded to the local community are given to contractors from outside the region.

The Penan have privileges for all the park area providing they are still nomadic. If settled their privileges revert to that of the Berawan. Unfortunately the settled Penan do not recognise the change in status, claiming that they are semi-nomadic and continue to hunt in all areas.

A few Penan families are still fully nomadic within the park but their exact number and whereabouts is presently unknown. Efforts to encourage the Penan to take up agriculture and domesticate animals have only been partially successful.

|  |  |

| Bat emergence from Deer Cave, Mulu Photo: David Gillieson | The Firecracker river passage, Clearwater Cave System | Rudang Gallery with massive sediment banks,Black Rock Cave |

The Penan consider domesticated animals as pets and are reluctant to slaughter them for food. Wild meat is clean meat so the park is still full of Penan hunting. Even small animals and birds are now killed. Both the Berawan and Penan have gazetted privileges to hunt and gather within certain catchment areas of the park.

The way forward was to integrate the local community in all aspects of the park; management; work opportunities; contracting and tourism included, (Liam and Gill, 1999).

I therefore started regular training courses for Tour Guides and introduced a Freelance Guides Licence for both Penan and Berawan (Gill, 1995, 1997, 1998 and 1999). This was highly successful and reduced the impact of illegal activities. Unfortunately a higher authority abolished the scheme and the Mulu youth went back to bird nesting.

The 528 square kilometres of the park area is only a remnant of the former forests, and is far too small to provide food for the growing population and the biodiversity is suffering severely as a consequence. Illegal bird nesting is of growing concern and has escalated over the past few years.

Many of the caves are trashed, strewn with graffiti and refuse. The population of cave swiftlet's is reducing in numbers dramatically and the endemic cave fauna trampled under foot.

The Penan Primary School at Batu Bungan seemed to be the hoped for breakthrough, education of the children in order to integrate them into mainstream society seemed the key. Along with colleagues from the UK, I set up and administered the Penan Children's School Fund. The money donated by many individuals from the UK was entirely spent on the children and school needs.

The purchase and distribution directly to the children of books; uniforms; school bags etc., encouraged the children to go to school. The school has almost one hundred children at the present time from seven to twelve years old.

Last year the first group of seventeen Penan Primary 6 children were transported from Mulu to the Secondary School at Long Panai by the writer and booked into Form 1.

All expenses; school fees, uniforms, shoes, books etc were paid for from the fund, with the promise of continuing support providing they did well. Long Panai is a boarding school and a long way from their homes. Homesickness over the past year and my absence has sadly reduced the numbers down to seven, but at least it's a start in the right direction.

The Management Plan

The first management plan was compiled by the Royal Geographical Society, London, (Anderson, Jermy and Cranbrook, 1982) and was the result of the joint Sarawak Forest Department and Royal Geographical Society expedition to the Gunung Mulu National Park, during 1977-78.

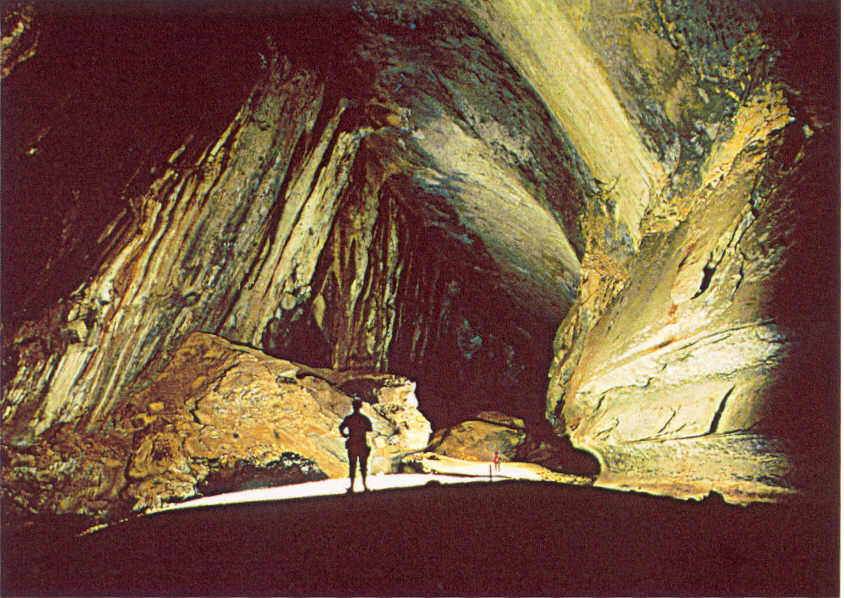

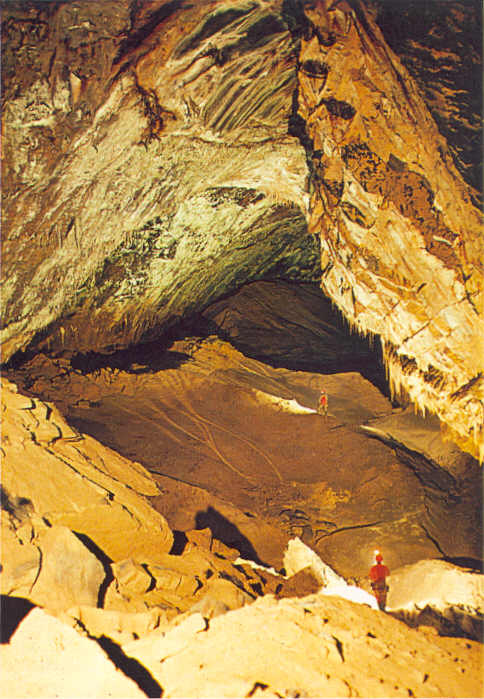

This plan concentrated for the most part on the significance of the flora, fauna, geology, geomorphology, hydrology and caves etc, with species lists. The caves proved to be spectacular for their huge dimensions and placed Mulu firmly on the map as a site of international importance.

Many UK based speleological expeditions and cave science projects followed which added to the importance of the park. The Clearwater Cave System became the longest cave in Asia at 110 kilometres in length.

Probably the most exciting discovery being Sarawak Chamber, the largest chamber in the world. Since 1978 over 300 kilometres of cave passage has been explored and mapped.

The second management plan, compiled by the Sarawak Forest Department, covered the period 1993 to 1995. (1992).At a meeting with the Minister of Tourism, Datuk James Masing in 1998, a discussion took place on the threats to Gunung Mulu and the comments made by Peter Hitchock at the Malaysian World Heritage Seminar. I was asked to attend the meeting and instructed to write the new management plan for Niah and Mulu with professional help. Both Prof. David Gillieson and Prof. Derek Ford kindly offered to assist and review the plan for a very minimal sum.

On the completion of the World Heritage Nomination document in June 1999 I was able to start work on the project but a short while later it transpired that the Danish Conservation and Environmental Agency offered to fund the management plans for four Sarawak National Parks that included Niah.

A contract to compile the management plan for Gunung Mulu was finally awarded by the state government to Borsarmulu Resort Sdn Bhd who in turn employed Manidis Roberts (Australia) as the main consultant.

By this time I had left the government service being unable to obtain a new one-year contract and took up employment with Ranhill Bersukutu Sdn Bhd, the engineering consultants for Gunung Mulu development projects. Working as the site engineer at Mulu I was still in a position to be of service to the National Parks and Wildlife Division.

After an approach by Borsarmulu Resort Sdn Bhd, nine years of hard won base line data for the park was supplied to the consultants, on the promise of taking an active role in the compilation of the new management plan. When the huge amount of relevant data requested was supplied, I was told my services were no longer required.

I have had the opportunity of reading the draft which is without doubt a professional and excellent basic plan considering the very limited time the consultants had to compile it and their limited knowledge and complexities of the park. It seems doubtful that the consultants had the time to read all the data supplied to them and of course numerous reports tucked away in Forest Department files were not supplied.

Of particular merit though are the sections on community participation, karst catchment areas and buffer zones, fully backing my long-term concerns for the local community and extensions to the park boundary. There are of course inevitable omissions and mistakes but the plan has satisfied the UNESCO criteria for Gunung Mulu World Heritage Status. It is worth noting that privatisation is considered as the best management option.

It will now be up to the new managers of the park to write the comprehensive plan of management for Gunung Mulu using the criteria of the basic plan as their reference. A very competent, experienced, understanding, knowledgeable and professional staff will be required in order to comply with the terms of the plan, as it is rather prescriptive in its approach.

Epilogue

The final outcome was that my services to the state were no longer required, which culminated in deportation from Sarawak, although no reason was given. This was probably due to the problem that occurred between the recently formed Sarawak Biodiversity Center and the joint venture USA, Sarawak Forest Department Speleological Expedition to Gunung Buda. This project had been monitored by the writer on behalf of the Forest Department and was normal practice over the previous nine years. Briefly the applied-for collecting permit never materialised and a substantial fine was imposed on the USA team.

The entire cave fauna collected, vital information for the future management of the Buda caves was confiscated and is probably now lost to science. It was considered as of great importance to identify the similarities between the cave fauna of Buda, compared to that of the Mulu caves as the Medalam Gorge truncates the limestone blocks.

The Gunung Buda Caves Project has been on going for the past six years and over 80 kilometres of outstanding caves have been explored and mapped. It goes without saying that this important project for Mulu has now come to a sudden and drastic end. Gunung Buda in its own right can be classified as of international importance as the most cavernous area of tropical karst known.

I submitted proposals for a Gunung Buda National Park four years ago, (Gill, 1996) which was accepted by the Sarawak State cabinet the following year. The park was finally constituted in the year 2001. Bordering to the north of Mulu, all the Melinau limestone region and caves are now safeguarded under park management, greatly enhancing the integrity of the Gunung Mulu National Park.

An unfortunate set of circumstances lead to the deportation. A sub contractor to the Australian management consultant submitted an ill-informed, unprofessional report on the development projects at Gunung Mulu. Also an email from the USA team explaining the events of their arrest and fine was sent to me. This was forwarded to the Forest Department but unknown to me it was also sent to 20 people on my address list by what later transpired to be a "worm virus".

A great deal of support and encouragement was received from two high ranking State Government Ministers, State Assembly Members and of course the Forest Department, but all to no avail. After six months of trying the deportation order still stood and myself and my Malaysian family were forced to flee the country leaving everything behind, including our home. Sadly the Penan School Fund has also been terminated, as I am no longer in a position to help the children.

|  |  |

| View from the Batu at Long Pala, looking along the Melinau Paku Valley towards Gunung Mulu summit | Aerial view of the entrance to Deer Cave, Mulu. Photo: David Gillieson | The Karst of Gunung Api |

The Future

I have recently presented a proposal paper on a trans-boundary Mulu, Brunei World Heritage Park to the Brunei Darussalam Forest Department as recommended by the IUCN. Unfortunately at present there seems to be little interest in this project. Possibly in the future this may be considered, as this would greatly enhance the Gunung Mulu National Park and its biodiversity with great benefits for both countries.

It remains to be seen what happens next. It seems probable that the park will be privatised and run by the Royal Mulu Resort and a Resort General Manager appointed to manage the World Heritage Park. It goes without saying that although having served the Sarawak State Government for nine years, also obtained World Heritage Status for Gunung Mulu and finally thanked by being deported, I still fully support the World Heritage Nomination.

The tropical karst and caves of Gunung Mulu and Buda are outstanding world examples and Mulu and the local community deserve the worldwide recognition that World Heritage Status will bring. Success or failure now rides on an effective professional management regime for the World Heritage Gunung Mulu National Park.

It is not going to be an easy job as Mulu is an extremely complex tropical forest and karst environment with a whole range of local community based issues to be addressed.

I can do no more but to wish Sarawak, the park and its people well.

Acknowledgments

The author greatly acknowledges the reviewers of the main documentation for the Gunung Mulu National Park World Heritage Nomination, Profs. David Gillieson, Derek Ford and Elery Hamilton-Smith for their invaluable assistance. Also the Senior Assistant Director of the Sarawak Forest Department and Head of Sarawak's National Parks, Sapuan Hj Ahmad for assigning the project to me and his constant encouragement, support and assistance.

References

Anderson, J.A.R., Jermy, A.C. and Cranbrook, The Earl of. 1982. The Gunung Mulu National Park Management and Development Plan. Royal Geographical Society, London. 291pp.

Bennett, E.L., Gumal. M.T., Robinson, J.G. and Rabinowitz, A.R. 1996. A Master Plan for Wildlife in Sarawak. Wildlife Conservation Society and the Sarawak Forest Dept. 347pp.

Ford, D.C and Williams, P.W. 1989. Karst Geomorphology and Hydrology. Chapman and Hall. 601pp.

Gill, D.W. 1995, 1997 and 1998. Gunung Mulu National Park, Guides Training Manual. Karst M. U. Sarawak Forest Dept.

Gill, D.W. 1996. A proposal to constitute the Gunung Buda National Park. Sarawak Forest Dept.

Gill, D.W. 1998. A Brief Proposal Paper for the inclusion of the Gunung Mulu National Park as a UNESCO World Heritage Listed Site. Sarawak Forest Dept.

Gill, D.W. 1998. Summary Paper for the Gunung Mulu National Park Nomination for World Heritage Listing. Sarawak Forest Dept.

Gill, D.W. 1999. The Gunung Mulu National Park Nomination for World Heritage Listing. Sarawak Forest Dept. 216pp.

Gill, D.W. 1999. A History of Guide Training at the Gunung Mulu National Park. Hornbill, Proceedings of a Workshop on Sarawaks National Parks and Wildlife. Sarawak Forest Dept. No.2.

Liam, J. and Gill, D.W. 1999. Community participation in the Gunung Mulu National Park: A case study. Hornbill. Proceedings of a Workshop on Sarawaks National Parks and Wildlife. Sarawak Forest Dept. No.2.

Sarawak Forest Department. 1992. Gunung Mulu National Park Management Plan, 1993 to 1995. Sarawak Forest Dept. 87pp.