Preface

This article has been edited from a much longer paper which will, in final draft, encompass all the known sea-caves and karst along an 800 kilometre coastline. It will be presented in two parts over two editions of this journal, with discussion about management issues being in Part II. The selected examples are a cross section of cave and karst types only. Readers interested in the full work should contact the author. A full bibliography is available and research is ongoing. Special thanks to Les Wright of Punakaiki for his help so far.

Impetus for the article came from a visit to the Punakaiki Pancake Rocks at New Year 2002 with fellow Poutini Potholers. Thwarted by a month's ongoing rain from caving at most local haunts including Bullock Creek, discussion with those present while watching the onslaught of the sea on the rock, centred around "just what" caves there might be running back behind the main surge pool and any links to known caves and grikes inland. I suspect that between the annual 3 metre rainfall busy dissolving the limestone and the sea busy eroding it, the area between the limestone bluffs and the coast (about 600 metres) might be just one big honeycomb. A 4 metre deep hole opened up about 1995 under the Department of Conservation's Punakaiki Visitor Centre, much to the consternation of staff and the delight of local cavers. The hole is still there, with its softer innards being literally sucked out from below. When will it go? And where? Karst geological processes are far from static. On a lee shore, with continual robust weather off the Tasman, little is sacrosanct. Management of any sea-caves and coastal karst throws up it's own peculiar problems. In some cases, management is impossible as edifices and caves disappear. Sometimes the only recourse is accurate documentation for posterity.

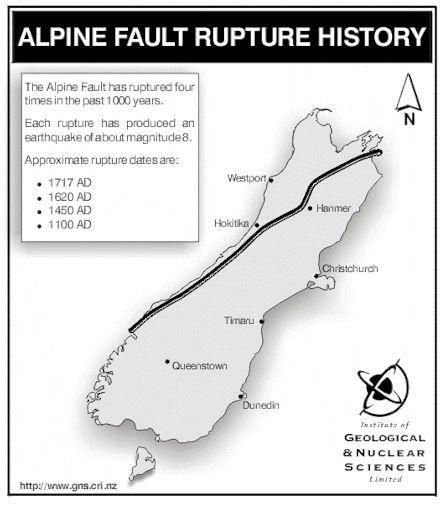

Finding good maps for the reader to refer to in conjunction with this article has been difficult both for space reasons and relevant detail. At minimum it might be good to have a map of the South Island to hand. Recommended is the large Heinemann N.Z. Atlas or at least a School Atlas map of the South Island. Information about the Alpine Fault is available on the Internet.

Introduction

The West Coast of the South Island of New Zealand has a long, rugged shoreline constantly buffeted by prevailing south-westerly weather from the Tasman Sea. Going into the 21st Century the sea is eroding the coastline along almost it's entire length with long established beaches being eaten away and cliff and headland areas in many places in states of collapse. North-westerly storms from the Tasman associated with spring high tides wreak periodic havoc, bringing down pillars of rock, stripping beaches of sand and "worrying" stop banks and seawalls built to keep the sea back. In many places beaches are non-existent at high tide and some coastal dwellings and roads are very vulnerable between Greymouth and Westport. Also vulnerable are the many sea-caves and karst areas along the whole coast.

As an example a month's steady rain over the 2001 Christmas period caused a major slip which has taken out half the road for 200 metres at Ten Mile, just north of Greymouth. The road, some rock, soil and vegatation have all slipped off the underlying steeply dipping Island Sandstone right down to sea level, causing a major headache for local roading engineers. The bottom of this ramp of rock is also quite undercut by wave action, almost to the full width of the slip, forming a large shallow cave. Only 80 metres south is an historic sea-cave which Charles Money waxed lyrically about in his book Knocking About New Zealand (published 1871). After a hard day's travelling north from the Mawhera Pa (Greymouth) to the Buller in 1862, he found the evening refuge "a most charming spot" with its view of a weather beaten rock (at the mouth of Ten Mile Creek) and waves roaring and surging almost to his feet as he sipped a pannikin of tea. Further slips could bury the mouth of this cave [Illustrations 1 & 2].

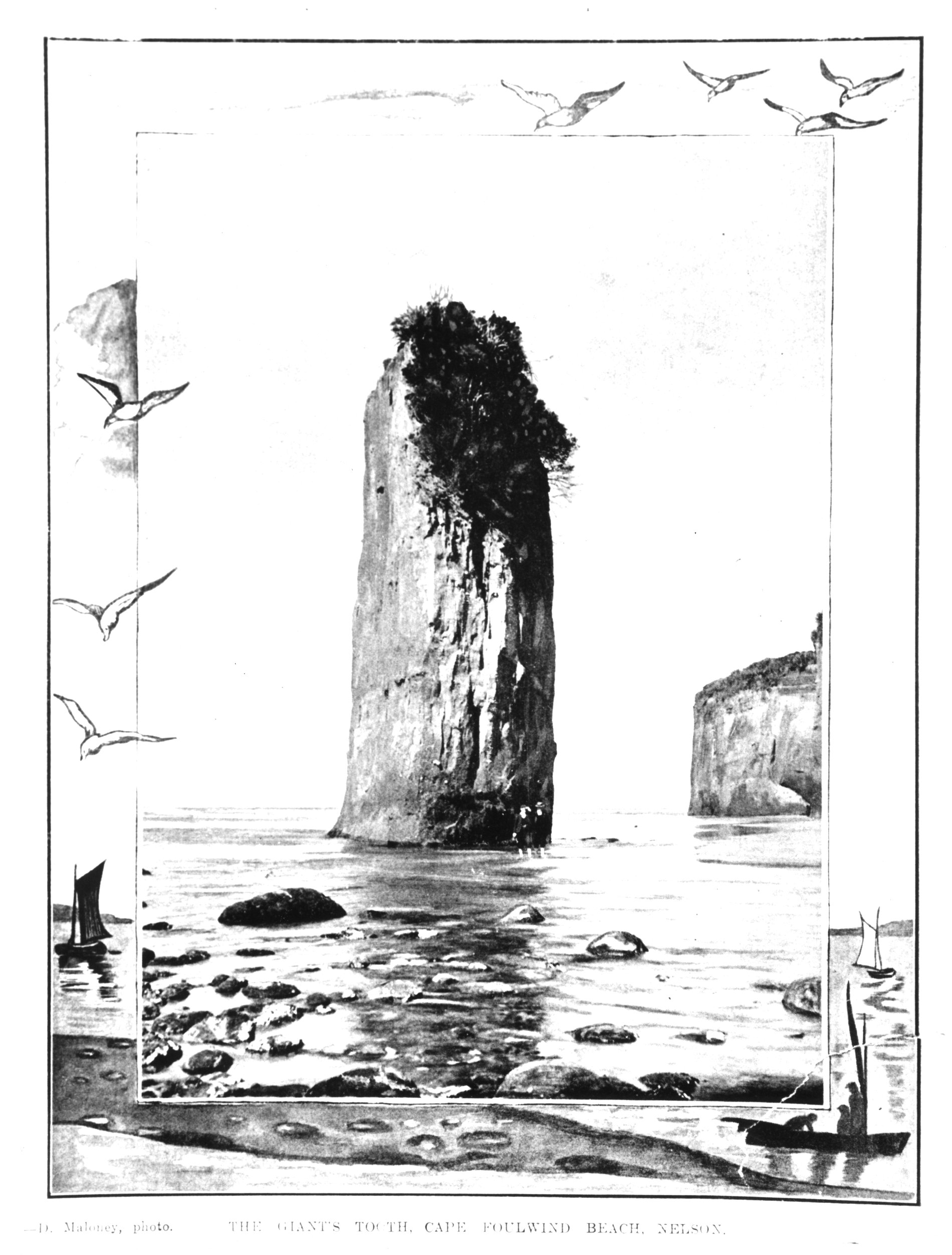

There is also is ample evidence that documentation of vulnerable coastal features is necessary. At just one location near Cape Foulwind, two historical sites formed in calcareous mudstone have both disappeared over the 150 years since Europeans came to the West Coast. A small cave at Kawau Point recorded by Charles Heaphy in his diary in 1846 is "no longer" while a large sea-stack, known as the Giants Tooth began to disintegrate after the 1929 Murchison Earthquake and had disappeared altogether by 1939. One is recorded for posterity in a diary while the other can now only be seen on old postcards and photographs such as that featured in the Otago Witness on Christmas Day 1905 [Illustration 3].

This article was initially to be about karst areas only but "as a cave is a cave is a cave whatever", the scope of the article has been extended to sea-caves in other rock strata because of their importance in early West Coast history. For those unfamiliar with the West Coast the whole area was, and still is in most places, heavily bushed with a rugged, mountainous hinterland. The coastline with it's many beach sections was the preferred route north to Golden Bay for the few pre-European Maori living in small villages located near the mouths of most of the larger rivers. However even on the coastal route there were some horrendously difficult headlands to get by, usually only overcome by the use of ladders roughly lashed together from whatever local materials were at hand such as rata vines and flax.

In the explorative phase of the 1840-50s and the early goldmining period of the 1860-70s, there was little change from the Maori mode of travel on land until rough tracks and then roads were cut to bypass difficult headlands. Sea-caves of all kinds were often therefore used for shelter by explorers, sealers, goldminers and "folk just passing through" as they waited for tides to turn and the rain to stop - the mean annual rainfall at Greymouth midway down the coast is around 2500mm (100 inches) per year.

After some deliberation about just what constituted the "West Coast" it was decided to include all the coastline (about 800 kilometres) to the west of the Alpine Fault (see map) thus leaving out any discussion, at this point, of caves and karst in Fiordland. In fact this works out very well as all the karst found west of the Alpine Fault is of Tertiary origin, being mostly limestones from the Oligocene period, while nearly all the karst in Fiordland has been metamorphosed to marble. The only exception is a small area of Paleozoic limestone in the far south at Preservation Inlet. Readers interested in coastal karst and caves in Fiordland are recommended to read Fiordland Explored by John Hall-Jones or Port Preservation and The World of John Boultbee, by Charles and Neil Begg.

For those unfamiliar with South Island Geology the Alpine Fault is a major fact of life. Tectonically those who live to the west of it are situated on the Australasian Plate while those to the east, where the Southern Alps are being uplifted at a steady rate, reside on the Pacific Plate. The two are not only colliding, so that the Southern Alps are still being pushed up, but slipping past each other to the extent that one geologically distinct area has been dislocated into two in the way distant past, leaving the ultramafic Red Hills of West Otago and the ultramafic Dun Mountain near Nelson, separated by some 480 kilometres [Illustration 4].

On this elongated coastal strip some of New Zealand's oldest rocks form basements for much younger Tertiary sediments. Pockets of Oligocene age Takaka Limestone in Kahurangi National Park overlie an ancient peneplain formed of Karamea Granite while further south around Punakaiki, Oligocene age Potikohua Limestone, which forms the well known Pancake Rocks, overlies Lower Paleozoic Greenland Group sandstones (or greywhackes). Other sediments deposited on the coastal margin post Paleozoic, but prior to the Oligocene limestones, include breccias, coal measures, mudstones and calcareous sandstones such as Island Sandstone. This rock is so calcareous in places that it has formed quite good caves such as those found at the bottom of the Truman Track north of Punakaiki, and Cavern Cave at Dunollie which is used for Adventure Tourism.

In the southern part of the study, where the coastal strip between the Alpine Fault and the coast is much narrower, the picture is generally similar with the smaller Jackson's Bay and Gorge River Oligocene limestone areas resting on Paleozoic sandstones akin to the Greenland Group rocks further north. The one exception to this occurs between the Paringa River mouth and Abbey Rocks where the strongly foramineral Abbey Formation is early Eocene. This in turn lies over an early Paleocene volcanic, the Arnott Basalts in which an historic cave, associated with the early sealing days in New Zealand, has been formed at Arnott Point.

Those who have looked at a map will now note that there is a long stretch in Central Westland without coastal karst. This coincides with the "Beech Gap" which extends south from the Taramakau River to the Paringa area of South Westland. The lack of both beech trees and limestone is directly related to repeated glacial action in the Quaternary period. In fact glacial gravels cover much of the Cobden Limestone on both sides of the Taramakau River, this being the strata forming Point Elizabeth with its caves and seastacks. Careful checking of the Archaelogical Sites Register has revealed only one cave along this "limestone gap" section of coast and this has been formed by glacial action in a huge greywhacke boulder dumped by a receding glacier behind the beach north of Okarito Lagoon. Artefacts retrieved from this site show it was much used by Maori as it was right by excellent food sources and fresh water.

Study Sites (these run north to south)

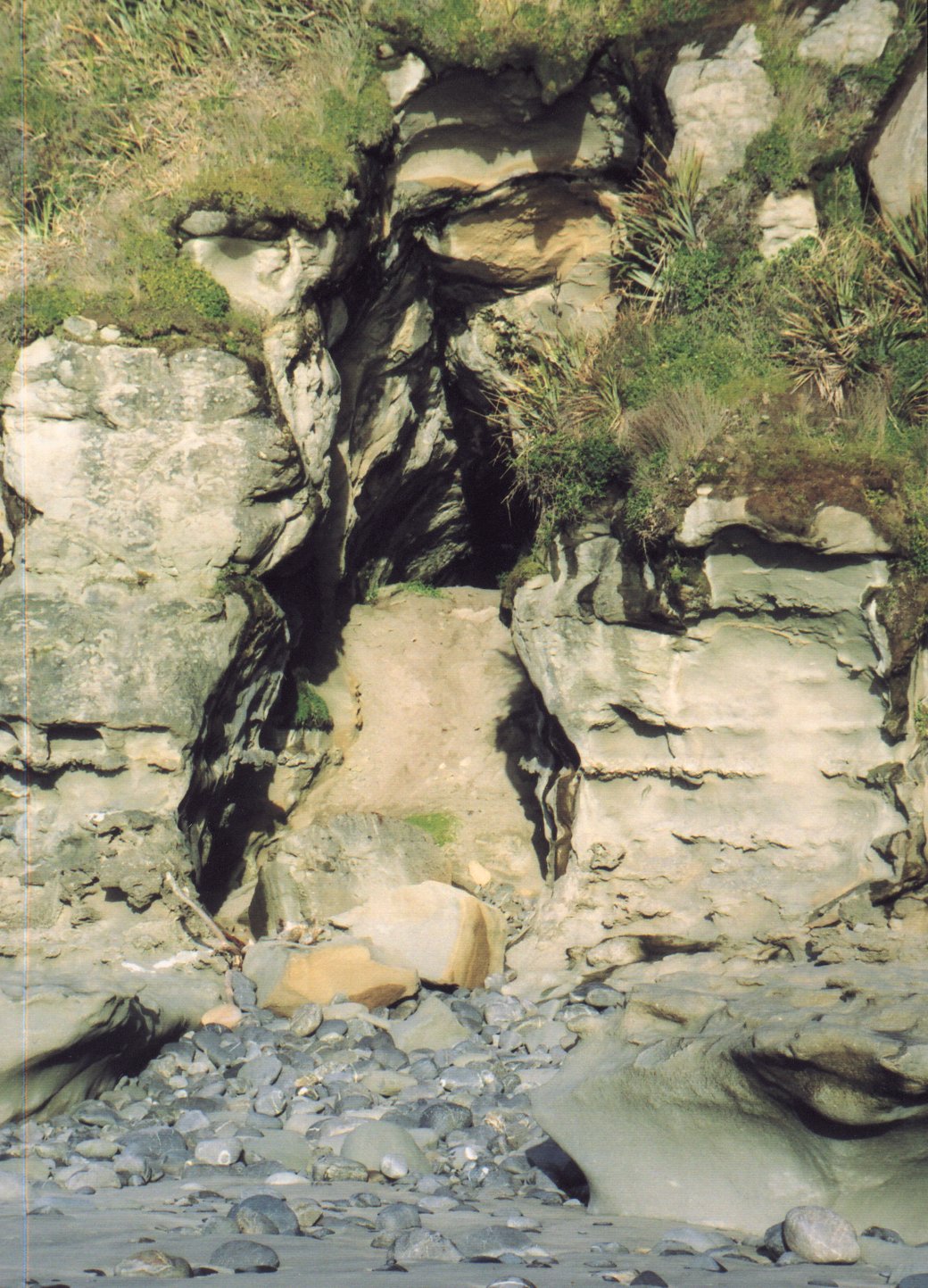

1. Sea-Caves of the Patarau - Sandhills Creek Area, Northwest Nelson

In this area Takaka Limestone is overlain by Kaipuke Siltstone (both Oligocene) with some Quaternary dune formations forming beaches between rocky sections of coastline. The limestone is a hard, crystalline rock, apt to be sandy in the lower parts of the 40 metre thick strata, and highly cavernous while the siltstone is a calcareous and fossiliferous mudstone. When travelling along any sections of this coastline one comes across small cliffs in either the mudstone or limestone with arches, small caves, rocky reefs, sections of wide sandy beaches (at low tide) and ample opportunity to explore for interesting fossils [Illustration 5].

That some of the caves were used in the past by Maori can be shown from the number of artefacts found in the area. Herbert Prouse, original landowner of the first farm immediately north of the Patarau River, collected a great number of artefacts including adzes, chisels, fishhooks, pounders, combs and pendants from sea-caves adjacent to his farm between 1904 - 1926. The collection was carefully maintained by his daughter Emma (Annabell), until she bequeathed most of it to the Nelson Museum in 1998, retaining just a few items for the current generation of the family. Similar artefacts have also been found in three small sea-caves which are all registered archaeological sites. These are located south of Sandhills Creek at the far end of the bluffs running behind the beach. The largest is a big shallow sea cave with a considerable build-up of sand which has banked up across half of the cave mouth. When excavated by archaeologists a few years ago the bank revealed material which may have been bedding or the remains of a fishing net. Currently the sand bar across the cave mouth appears stable and not prone to sea erosion but Ian Millar, DOC Nelson, feels if erosion did occur, the site's archaeological values would be lost quite rapidly.

|

|

|

| 1. The big slip from the Coast Rd. to sea level near Ten Mile Creek north of Greymouth. The slip down the dip slope of the Island Sandstone is only 80m north of an historic sea-cave which is behind the rocks in right foreground of photo. | 2. Charles Money, an early European wayfarer, spent an idyllic evening in this cave in 1862 . The cave is easily accessed along Nine Mile Beach at low tide. | 3. "The Giants Tooth", which stood about 16 metres high off Cape Foulwind, finally disappeared into the sea about 1939. This postcard picture, by an unknown photographer, was published in the Otago Witness, Christmas Day 1905. A photograph of the original postcard, loaned by a Westport resident has been computer scanned for this article. |

2. "The Wineglass" near Kongahu Point

Between Little Wanganui and the Mokihinui River lies the Karamea Bluff. Travellers taking the coastal route in the old days found parts of this rough going and eventually inland routes over the bluff, including the modern road, were made. The current 1:250,00 geological map shows much of the terrain between the road and the coast as mudstone or limestone and this is borne out on page 186 of P. G. Morgan's The Limestone & Phosphate Resources of N.Z., 1919, which says, "South of Corbyvale argillaceous limestone outcrops on the New Inland Road from Seddonville to Karamea ... Highly calcareous claystone or argillaceous limestone outcrops in the valleys of Six Mile and Three Mile Creeks ... And the same type of rock forms the conspicuous cliffs at Gentle Annie and Kongahu Points."

However despite this limestone there are no known inland cave systems, no registered archaeological sites and only one small sea-cave at the southern end of the bluffs at Gentle Annie. On the other hand most people travelling the beach route (popular today with trampers) comment on the huge blocks of limestone lying on the beach around Six Mile Creek and northward toward Kongahu Point. These blocks lie below a very notable landmark in the form of a huge landslip which can be seen 18 - 20 kilometres out to sea.

White in colour, this slip has a very distinctive shape, in fact Westport fishermen such as "Flag" (Ian) McKenzie, know it as "the Wineglass" [Illustration 6]. Charles Heaphy on his 1846 explorative trip south along the coast with Thomas Brunner and their two Maori guides, knew about this slip in advance because the party's limited charts showed the three cliffs of Otahu with a note "Very steep coast, remarkable fissure." Heaphy also commented in his diary that on April 24th: (they) "Crossed the Tunapoho glen and stream (Six Mile Creek), and ascended the Otahu hill in order to avoid a deep chasm in the beach. The hill is about 1,100 feet in height, and the ascent is by a watercourse, over slippery clay and limestone. The way continues along the summit for about a mile, and then descends the face of the hill by the landslip before mentioned, being the most laborious and one of the most dangerous portions of the route between Cape Farewell and Kawatiri (Buller River)."

This is a very large slip, at least 200 years old and not at all your regular type of karst "formation." A possible cause of the slip is that an old cave system, based around the Six Mile Creek limestone has collapsed, spilling blocks of limestone rock down onto the coast below. This could have been precipitated by either the heavy rain which the West Coast is well known for or a large earthquake or both. If an earthquake was responsible it may have been associated with the last major rupture along the Alpine Fault which N.Z. Geological & Nuclear Sciences Institute geologists estimate occurred about 1717. What is definitely known is that the 1929 Murchison Earthquake, Magnitude 7.8, caused major havoc in this general area and Karamea was cut off by road for months afterward. The area warrants more investigation by cavers as it is known that below Corbyvale a stream disappears underground in the vicinity of the present Six Mile Creek limestone area. Somebody?

3. Fox River Sea-Cave

A somewhat unusual sea-cave exists at the mouth of the Fox River, unusual in that it is formed in Hawkes Crag Breccia [Illustration 7]. This is a Cretaceous formation named for its type site in the Buller River Gorge. The breccia, which is formed of irregular sized rocks eroded from the basement rocks of the area (Karamea Granites and Greenland Group greywhackes) cobbled together with coarse sand, occurs sparsely around the lower Fox River area with much larger outcrops upstream of the limestone gorges in Bullock Creek and the Porarari River. To some extent, the cave is sheltered from the prevailing south-west winds and accompanying heavy sea swells by Seal Island just to the south. Erosion does occur, as much from the river as from the sea, but is not currently a major problem.

In contrast to many of the sea-caves found up and down this coast this one is very accessible because the highway goes right by it just before crossing the bridge over the river. Greymouth people have long valued the area for picnicking and a number of small baches, which have been there for many years, butt right up to the south or landward cave entrance. It's not uncommon for picnickers to park their cars and head out to the sea or river beaches by going through the cave. Backpackers and cycle tourists are also known to stay in the cave by choice or if caught out between towns without shelter. Confirmed Westport conservationist Terry Sumner, who only owns a bicycle, regularly sleeps over in the cave on forays down the Coast Road. This cave is a "living one" with people coming and going through it all the time.

Heaphy gave this excellent description of the cave, when the exploration party passed through in May 1846, "Crossed the Potikohea stream, a mountain torrent, running strongly, and immediately entered a remarkable cavern, Teorumatu. A large mass of conglomerate rock, about 150 feet long and 80 feet high, stands out at the edge of the beach, and through its base this cave has been hollowed, apparently by the action of the adjacent stream, at some remote period ere the coast line had been elevated by volcanic agency, the signs of which are in many places apparent. The vault is in the form of a cross, and penetrates the rock at right angles from its four sides, the eastern entrance, however, being blocked up. It is about 30 feet high, 150 feet long, from north to south, and about 50 crosswise. In it the natives have erected bed places, and stages for the purpose of drying dogfish, which summer the people from Araura (Arahura) catch on an adjacent isolated reef."

These days the cave, which has long been registered as an archeological site, is mostly known by its "pakeha" name of Fox River Sea-Cave however in many historical references it is known by a variety of Maori names, most of them referring to natural features. Heaphy noted the name, as told to him by his Maori companions, as Te Oru Mata which means the hole or cave (oru) in the headland (mata). Another variation is Te Ana O Matuku with matuku meaning ngarara or giant lizard. The ngarara is reputed to lie in the cave waiting for passersby in order to eat them. However judging by the number of people who have stayed in the cave over the years this doesn't seem to have deterred very many travellers.

Over the 150 odd years since Europeans began to visit the West Coast use of the cave has continued. Goldminers holed up in it while waiting for the rain to stop and the river to drop on their way to Charleston or Westport. One early settler used it as a cow byre. In the 1950's there was a rush to stake out the cave area for uranium mining when it was realised that the Hawkes Crag Breccia carried traces of uranium ore: however this hunt quickly moved on to the more the more lucrative areas of similar breccia at Bullock Creek. On a totally different note the cave was used as a film set for the 1976 movie "Wild Man" starring Bruno Lawrence. This was the start of Lawrence's quite remarkable film career and the locals, many of them living at the quite large alternative life-style commune on the north side of the Fox River, got to act as extras although the low budget for the film meant they were paid in Rochdale Cider rather than hard cash! Happy days.

Management of the cave is somewhat of a problem in that continual traffic through it tramples relics and signs of past use. According to the Archaeological Site Records there's been quite a bit of amateur fossicking over the years to the extent that some artefacts were removed to the Canterbury Museum for safekeeping by archaeologists completing "official digs" in the 1970's while according to Twelve Mile resident Peter Hughson, a number of adzes were removed from the cave in the same period, storage place unknown. The 1965 Site Record notes some sea erosion of anthropogene deposits and signs of fossicking while the 1975 Site Record notes that "Boys were riding motorbikes through here during our visit and disturbing the floor and the sloping central edge within this cave!"

Even now that the Department of Conservation have taken over responsibility for the cave from Transit New Zealand, it is doubtful that established use patterns will change, although it is to be hoped that those who come here in future have enough sense of their heritage not to ride motorbikes through the cave. At the end of 2001 high tides backing up the river eroded an area inside the riverside entrance uncovering part of a large midden and exposing some dressed timbers which DOC and archaeologists are still puzzling over. If erosion uncovers aspects of past heritage is this a good thing or bad thing? Whichever, the outcomes can be recorded, monitored, photographed, speculated over but hardly controlled. The elements will carry on doing their "thing."

4. Perpendicular Point

Just north of Punakaiki is Irimahuwheri Bay with its high cliffs and the absolutely stunning Perfect Strangers Beach. This is very hard to get to as one has to hop round endless rocks from Meybille Bay or descend 300metres down a very steep track from the road. About halfway along the beach, heading south there is an abrupt change from Meybille Bay Granite to Island Sandstone, with a distinct line running almost vertically from sea level to the road. From here, facing south, one sees the full spectacle of the Te Miko cliffs or the Perpendicular Point cliffs as they are now called, which were a formidable obstacle in the days of foot travel. The Island Sandstone here is a lovely warm gold-coloured calcareous sandstone which weathers down to form wonderful coastal formations and sea-caves. A good sized cave one, which must have been used for shelter, can be found, just about as far round as one can safely get along the beach at low tide. This is in the vicinity of the once notorious ladders.

In the past many Maori, especially family groups, actually bypassed the cliffs by ascending where one drops down today from the road and then cutting across inland to get to the Porarari Estuary. But war parties or those in a hurry ascended the cliffs via rough ladders made of flax and rata vines. That these ladders, which were overhung and often rotten, gave the early explorers like Heaphy, Brunner and Julius von Haast the "fair heebie -jeebies," is borne out from all sorts of accounts in their various diaries. By the mid 1860s the goldminers prevailed upon the Nelson Provincial Government to "do something" so a chain ladder was put in but the rungs often broke and men found themselves sliding down the chains, sometimes to their death. Eventually contracts were then let for an alternative route suitable for people and packhorses and so the Inland Pack Track was born (another story).

A very good graded track, the Truman Track links the highway to the coast giving access to caves both north and south (about a kilometre either way). Heading back north, which is only feasible at low tide in fine weather, it is possible to reach a number of caves of which three, including Half Moon or Crescent Cave are registered archaeological sites. All have been used in the past by Maori for shelter and cooking in as evidenced by middens, oven sites, burnt shell and stones, and both stone and greenstone tools. At least one of these caves would have been a doubtful shelter at high tide in rough seas but the others are more secluded.

Heading south there are a number of small caves and a large double cave-cum grotto which one can get to by climbing down to from above or by carefully traversing along the wave platform. Facing out to sea and open to the weather, the cave is typical of the grottos and caves which form along here in the Island Sandstone. In the 1946 Automobile Association Canterbury Inc. booklet, The Road West there is a photograph of it taken from the air [Illustration 8] and captioned "Neptune's Theatre." Definitely a place to say you've been to.

|  |  |

| 4. South Island, New Zealand showing the Alpine Fault | 5. One of a number of sea-caves just south of Sandhills Creek, North-West Nelson where Maori artefacts have been found This cave, formed in calcareous Kaituna Siltstone is well above high tide level (at the top of the tongue of sand). It would still make a good shelter today if one were cut off by the tide. Nearby there are also many caves in the adjacent Takaka Limestone. | 6. This photograph of the Wineglass was taken by Ian McKenzie, Westport fisherman in the late 1990s. The slip is visible for up to 20kms out to sea and fishermen often use it as a quick check on their location when steaming up or down the coast. |

5. The Pancake Rocks of Dolomite Point

About 3 kilometres south of Perpendicular Point are the world famed Pancake Rocks at Dolomite Point. This name is a somewhat erroneous name as there is no magnesite to speak of here. In fact the original name of Cave Point is far more appropriate. In the vicinity of the Point the high quality Potikohua Limestone is stylobedded in it's upper layers to create the well known pancaking effect. The constant onslaught of the sea on these layers has created surge pools, blowholes, caves and arches not to mention some concerns for the long term management of the area because sooner or later there will be some spectacular collapses. Hopefully not at a time when there are busloads of tourists out there.

Deborah Carden, currently working for DOC at Westport and an ACKMA member, had the opportunity on a fine, calm day in the summer of 1996-97 to take a boat trip with local tour operator Ra Clay from the Fox River mouth, down the coast to Dolomite Point. Very, very few people get the opportunity to see the Pancake Rocks and the Blowholes this way so that her description is well worth repeating here. It is so different view from the general tourist's view of looking out to sea and waiting for the blowholes to "do their thing." In her own words she says:

"We floated around the north side of the Pancake Rocks headland then decided to take advantage of the lovely flat sea and go into the surge pool. We kept an eye out for rogue waves, as the surge pool is not also known as the Devil's Cauldron for nothing. To get an idea of what the western arch looks like one only has to look at the southern arch from where a huge chunk of rock fell in the 1980s. The progress of decay and collapse can be tracked from old photos. DOC built a bridge over the southern arch in 1997 so that if the arch collapses access can still be gained to the main blowhole, Putai [Illustration 9].

The underside of the western archway is a huge block and though I did not feel comfortable passing underneath it, I had a good look because DOC was interested in how stable it really was. The good old geologists gave us (DOC) a great report that said it could stay like it was for several hundred years or it could collapse tomorrow. Very comforting! It is checked after any earthquake and is photo-monitored each year.

After we exited the surge pool we went around to the main Putai blowhole and had a look under there - the tide was low so we could get a good look but did not go under as there wasn't enough space if a rogue wave came. This was followed by a short expedition into the Chimney Pot slot and a quick look at the next bay to see if we could see any sign of a possible cave that could go way back to the visitor centre...no such luck."

The whole blowholes headland can be depicted by putting one's hand flat on a table top, then standing the hand up with the tips of one's fingers touching the table and the main part of the hand arched. Spread the fingers so that there are five gaps through which the sea would rush if you were a pancake rock, blowing spray out at the tops in a southerly swell." Magic.

Magic is also the Pancake Rocks at midnight on a full moon with the phosphorescence of the sea coming and going with the swells. A night visit might just be on the cards for the 2005 ACKMA Conference. Anyone?

Part II of this article will include: Te Ana Puta at Point Elizabeth, The Lithographic Limestone At Abbey Rocks, Two Sea-caves in the Arnott Basalts, Karst of the Open Bay Islands and Caves of the Far South (Where is the Frenchman's Gold?!) plus a discussion about the pros and cons of managing all such places.

|  |  |

| 7. Fox River Sea-Cave is a most interesting place to explore. An archaeological site, it has sheltered many wayfarers, been a movie location and subject to close scrutiny for its mining (uranium) potential. The 20th century changes in sea-level are beginning to impinge on the formerly dry cave and it will probably become inundated again within the next 50 years. | 8. "Neptune's Theatre" is a large grotto in the Island Sandstone sea cliffs south of the Truman Track at Punakaiki. Visitors to the area more commonly visit the rocky bays and small sea caves (some of them Archaeological Sites) north of the track. | 9. The main surge pool at the Pancake Rocks at Dolomite Point, Punakaiki. The surge pool is rarely accessible by boat or sea kayak and where the caves behind the pool go is somebody's next adventure. |