India! What a wonderful, dynamic and often frustrating place! My family and I arrived in Bombay on 1st February for a month-long Indian sojourn. The first thing that strikes you about India (other than the pleasant low thirties daytime temperature) is the traffic - or more specifically the taxis and their drivers.

About half the vehicles in this city of 15 million people are taxis. The road rules are quite simple - there pretty much aren't any? It is fascinating (and initially a bit scary) to observe four Bombay taxis driving abreast on a two-lane carriageway, with horns constantly sounding ... Two things don't last in Bombay, clearly - brake pads and all but the fleetest-footed pedestrians (that latter of which, of necessity, I became).

|

|

|

Three tiered Buddhist |

Columns in a cave at Ellora |

The Ajanta mile post! |

We only had an overnight in Bombay at this stage, flying the next day to Goa - the former Portuguese colony about half way down India's west coast, which forcibly became a State of India in 1962. In Goa things are a bit slower, but not much. It's a wonderful, lazy place - full of coconut palms, magnificent beaches, and Pommy tourists - the latter of which arrive in droves on cheap charter flights from Manchester.

After ten days in Goa, we took the overnight sleeper to Bangalore (mid south India). The 300 km trip took fourteen hours! It wasn't that the train was particularly slow when in moved; it's just that it stopped more often than it went. After three days visiting my wife's cousin, we then flew to Cochin in Kerala (south east coastal bit of India), where we relaxed at a comfortable hotel for a few days, prior to spending an overnight on a houseboat (along with lots of mosquitoes) gliding through Kerala's lakes and rivers. It was very pleasant.

Then it was a flight back to Bombay for a week, prior to flying home - AND my visit to four cave sites! From what I can ascertain, there is no karst of any note in Western or Southern India, although there is evidentially a marble mine somewhere in Rajasthan (a state north of Bombay, in Western India), from which the marble for the Taj Mahal was mined. There is a bit of karst in the mid north, I'm told, but most of what exists is in the north-east, above Calcutta - a very long way from where I was.

What Western India does possess is about ten rock-cut cave sites, many of which are consider minor, but three of which are world heritage listed and quite magnificent, namely the Ajanta (pronounced 'are-junta'), Ellora, and Elephanta Caves.

Kanheri Caves

But before venturing to these three wonders, I decided to take in a trip to a handy "lesser" site - the Kanheri (pronounced 'canary') Caves. Kanheri is about 45 kilometres north of Mumbai (as Bombay is now called), barely outside the urban spawl, in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. Travelling 45 kilometres sounds easy, but it took two hours by train and auto-rickshaw and taxi to get there! But it was worth it. The area contains a bit over one hundred rock-cut caves - as with all of this Western India genre - chiselled out of basalt.

The word Kanheri reportedly originates from the Sanskrit word Krishnagiri. Krishna generally stands for black mountain. The caves date from the 1st Century BC to the 9th Century AD. Most of them are Buddhist Viharas meant for residence, study and meditation (i.e.: effective 'monasteries'). A few of the caves are Chaityas (temples for congregational worship) indicated by their internal rock-cut stupas. It seems that Kanheri Caves were in their time an important trading axis between India and the Western world, as well as effectively a flourishing 'university' and a reputed centre of learning. The caves contain nearly one hundred inscriptions, mostly in Brahmin Script. Collectively, these have made dating Kanheri relatively easy, as well as delineating the various stages of cave development.

|

|

Layout of the Ajanta Caves |

Diagram of the 'Main Cave' at Elephanta |

While important Buddhist monuments, the Kanheri Caves are collectively relatively small, compared to the sometimes-massive edifices that were to come on my trip. As with most rock-cut cave sites, their dating ranges over a long period, having been excavated (usually successively) at different times. The highest cave in the group is situated at about 1500 feet above the sea level, and the view back over Bombay through a gap in the hills is quite good (except for the smog ... sigh ...). Still, in total, the site does present a glimpse of the interesting history and the culture of Buddhist India.

Two days after my visit to Kanheri, I took the forty-five minute flight from Bombay inland to Aurangabad for two days - a small hamlet (by Indian standards) of about one million people. While only a few hundred kilometres from Bombay, I did not fancy the otherwise thirteen-hour train journey (involving several train changes) to get there. Aurangabad is 'central' for visiting the glorious Ajanta and Ellora Caves - respectively 100 kms and 25 kms from the city.

Ajanta Caves

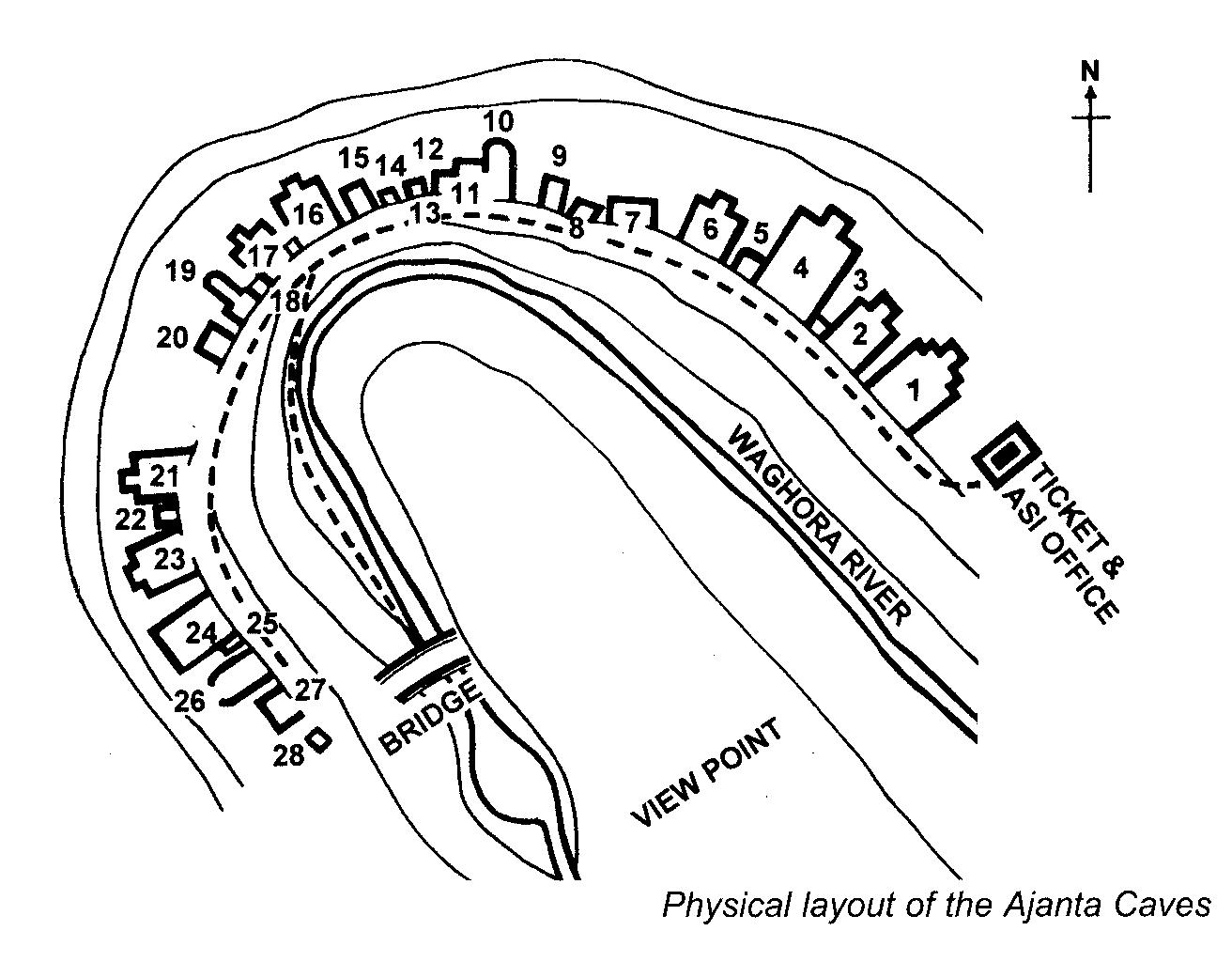

Arriving about 8.30am at my hotel, I immediately took the 9.00am bus tour to Ajanta. Three hours later (!) we covered the 100 kms and arrived - though the countryside was interesting (at least on the way). Clearly the relatively recent beneficiary of world heritage money (one suspects), we began at a garden carpark - full of modern, clean shops (not overly common on both counts, in my Indian experience thus far, and subsequently). We were then sent in 'resort' buses the four kilometres to Ajanta. I knew we had arrived, because as I stepped from the bus I noted a milepost on which was inscribed: Ajanta '0'. Just one of many quaint and mildly curious things about India.

In having paid my 250 rupees entrance fee (approx nine Australian dollars) - Indian citizens only pay ten rupees, fair enough I suppose - I ascended the long steps to the site.

|

|

|

A view inside the massive Kailasa Temple |

A View inside 'Main Cave' at Elephanta |

The Hindu God Shiva - 'Main Cave', Elephanta |

The rock-cut caves of Ajanta nestle in a panoramic gorge, in the form of a gigantic horseshoe. They possess some of the finest examples of earliest Buddhist architecture, cave-paintings and sculpture. As with Kanheri, these caves comprise Chaitya Halls, or shrines, dedicated to Buddha, and Viharas, or monasteries, once used by Buddhist monks for meditation and the study of Buddhist teachings.

While the architecture of Ajanta is stunning, the paintings that adorn the walls and ceilings of the caves are (to use an Elery-ism) wondrous! They depict incidents from the life of the Buddha and various Buddhist divinities. Considering their age, many are in relatively good condition. Amongst the more interesting paintings are the Jataka tales, illustrating diverse stories relating to the previous incarnations of the Buddha as Bodhisattva, a saintly being who is destined to become the Buddha.

The effective preservation of the Ajanta frescoes (or more correctly, tempura murals) is fortuitous. The caves were excavated between 200 BC and 650 AD. After a continuous occupation of about 850 years they were abandoned, rather abruptly it would seem, following the rapid decline/demise of Buddhism in the region.

Happily, from a preservation point of view, they remained shrouded in obscurity for over a millennia - overgrown and forgotten - till one John Smith, a British army officer, accidentally stumbled upon them while on a hunting expedition in 1819.

Even so, following their rediscovery so-to-speak, local villagers still managed to deface quite a few of the paintings in the interim, until they received complete government protection.

Ajanta and Ellora gained World Heritage listing in 1983 (the first listing in India, along with the Agra Fort and Taj Mahal in the same year). Elephanta gained its listing in 1987.

Ellora Caves

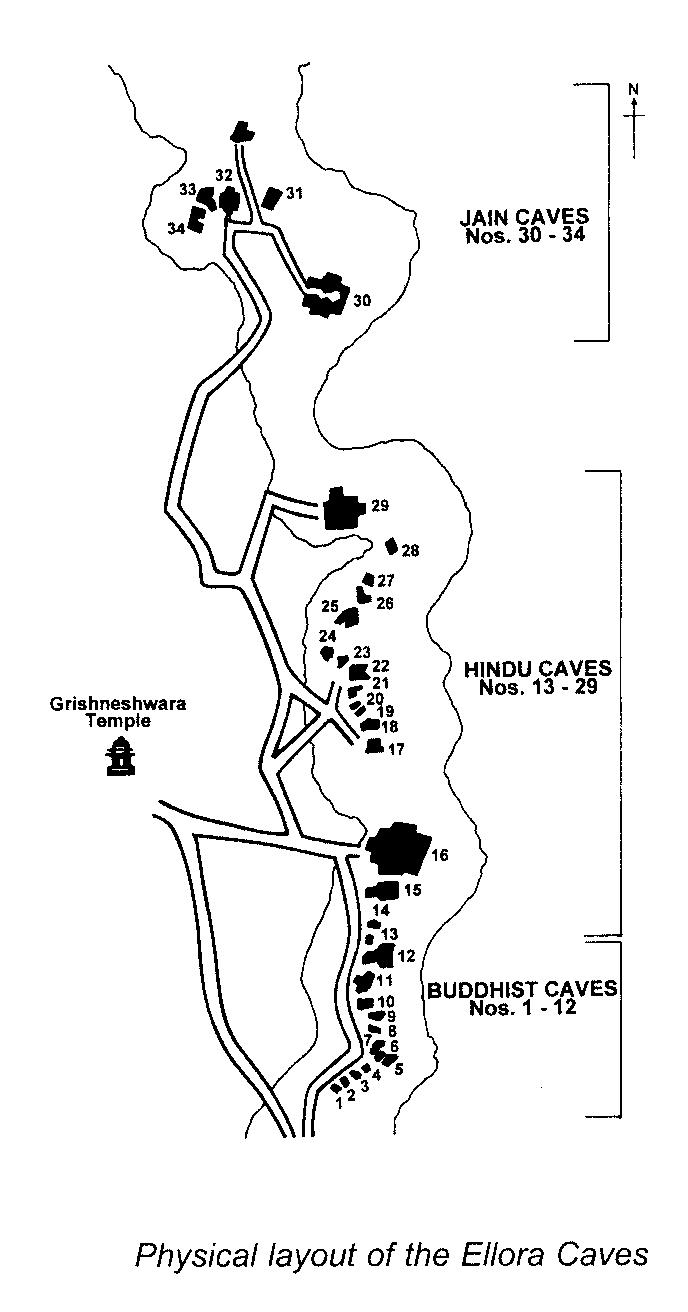

Having been 'blown away' by Ajanta, the next day it was off on a (quicker!) bus tour to Ellora. Similar to Ajanta, the cave temples and monasteries at Ellora were largely excavated out of the vertical face of a basalt escarpment. Extending in a linear arrangement, its thirty-four caves contain Buddhist Chaitya Halls, and Viharas, as well as Hindu and Jain temples.

Their excavation spans a period of about 600 years, between the 5th and 11th centuries AD. Without doubt, the most imposing and staggering (to use another Elery-ism!) is that of the magnificent Kailasa Temple (Cave 16) which is the largest single excavated monolithic structure in the world.

Unhappily, Ellora, unlike the site of Ajanta, was never 'rediscovered'. Known as Verul in ancient times, it has continuously attracted pilgrims (and sadly, vandals) to the present day.

As a result, unlike Ajanta, the frescoes that decorated the Ellora Caves have long-since been largely destroyed. However, while 'difficult', the glory of the architecture at Ellora surpasses that of Ajanta in my opinion.

The three Jain temples, geographically at the end of the group, were magnificiently fine - with rock carving having clearly risen to its peak. The design and intricacies of the Jain carvings, in particular, are quite breathtaking!

Cave Architecture

The caves at Ajanta and Ellora et al. where fashioned in great detail, much as a modern architect would. The techniques employed undoubtedly indicate a 'grand design' at work.

At Ajanta, the first step was to prepare the rock face. After selecting a suitable horizontal layer of stone, a large arch-shaped window was marked out. These horseshoe-shaped openings are instantly recognised when looking across the cave facades.

|

|

|

Elephant Carvings - Kailasa Temple at Ellora |

Murals in Ajanta Caves |

Monastery at Kanheri Caves |

The window, marked in outline, was then dug out, with the rubble utilised to fill the forecourt. This window allowed the stone-cutters entry to the bowels of hard rock. As the cavity increased, the ceiling was hollowed and the columns, which were to be finished as pillars, were marked out. These also served to divide the hall into aisles. Thus, the masons progressed downwards. One clear advantage of this modus operandi was that scaffold was unnecessary.

An interesting feature of the construction at Ajanta is that the decoration of the pillars, architraves, and walls was done simultaneously with the excavation of the basalt. The same workmen who shaped the monolithic pillars also decorated them and adorned the walls.

In addition to its functional use to allow access and the removal of rubble through it, the cave window in each case lit the interior with sunlight reflected on metallic mirrors pointed at apertures. The stupa-encasement preserving, in each case, a sacred relic of the Buddha, was placed right in front of this window to the rear of the cave.

The window being the only source illumination, the Chaitya hall was (and still is) suffused with a soft light, undoubtedly enhancing the mystic atmosphere the Buddhists were looking for.

Many caves at Ellora were constructed similarly, although some, such as Kailasa Temple (Cave 16) already mentioned, effectively were excavated vertically into the rock. Kailasa is a Hindu Temple, and it is immense.

It has been estimated that almost two million cubic feet of rock was excavated in its construction, and took an estimated 150 years to complete, being over 1200 feet in depth at its lowest point from the rear cliff face!

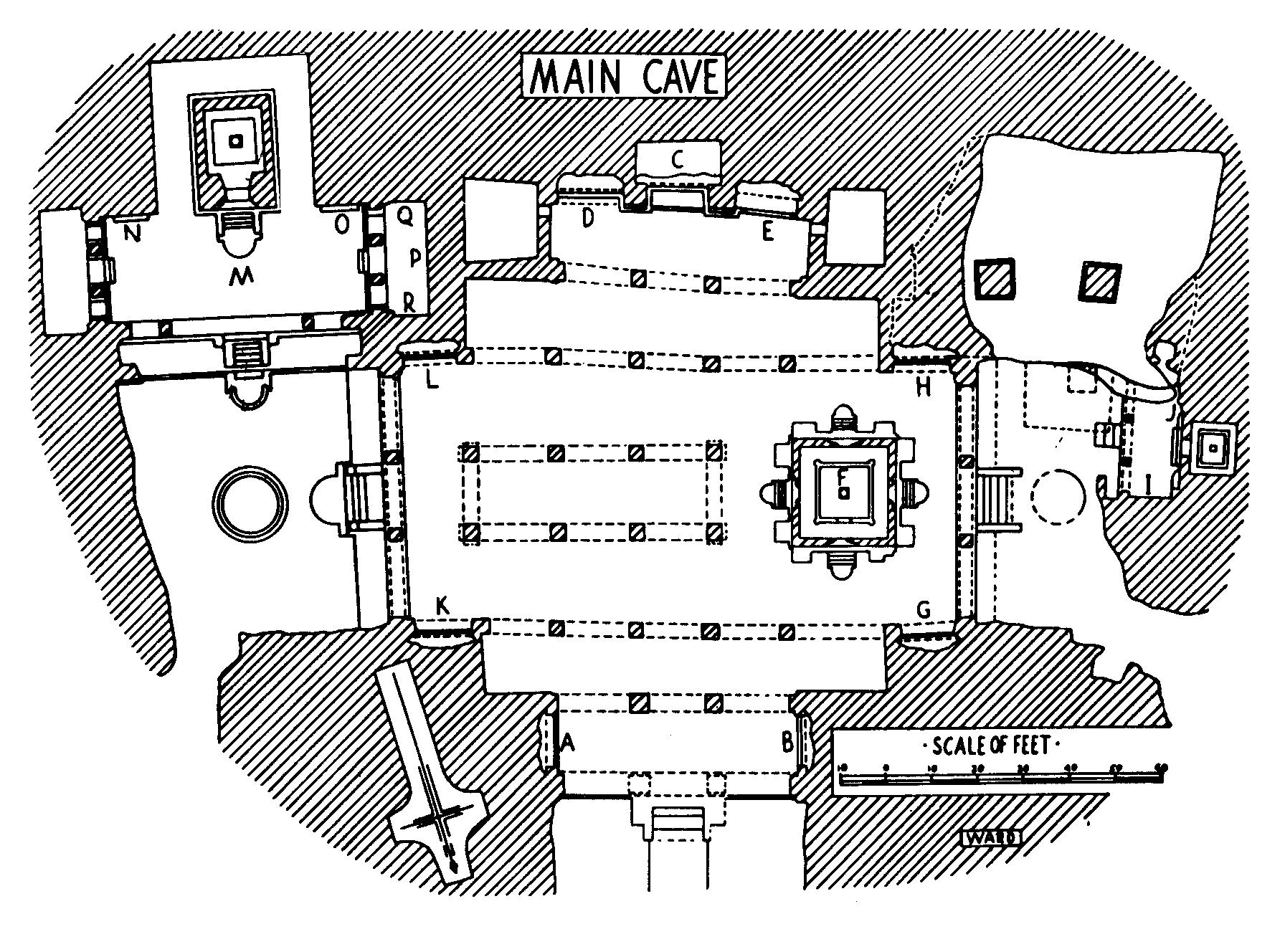

Elephanta Caves

Upon returning to Bombay from my two-day jaunt to Augangabad, I next ventured to Elephanta Caves, located (as they would be) on Elephanta Island - which is a one-hour ferry trip away out into Bombay harbour. I took a wooden hulk euphemistically described as the 'delux ferry' - and it was compared to the comparatively appalling craft used for 'economy' passengers ...

Upon arriving at the dock, one can either walk to the base of the steps (maybe 600 m) or take (for a few rupees) the "toy train". I took the train, and I am glad I did, as the path up consists of at least a kilometre of fairly steep steeps - crammed on both sides with tourist traps full of very pushy trinket sellers. Having run (or rather staggered up) the gauntlet of these (having been in India some weeks I was largely use to them), I reached the apex and the "main cave" - which everyone sees. There are also evidently a few minor caves on the island.

I must admit, while Elephanta was tremendous in its own right, it was somewhat 'tame' after Ajanta and Ellora. It is a very big cave - not as huge as some at Ellora - but very sizable nonetheless. Its main (pillared) hall was particularly impressive, as were several of the Hindu carving on its walls.

Very little is known about the history of the Elephanta Caves, other than it was excavated in 8th century AD. The name "Elephanta" is derived from a colossal stone elephant found on the Island, which a guidebook advised me was now to be found in the Prince of Wales Museum in Bombay. The next day I visited this museum (its external architecture is great, its contents largely not, in my view) to feast my eyes on the said giant stone Proboscidea. Sadly, I was informed this, one of India's greatest treasures, resided in basement storage and was not on show. Sigh ...

|

|

|

An Ajanta Cave showing its 'cave window' |

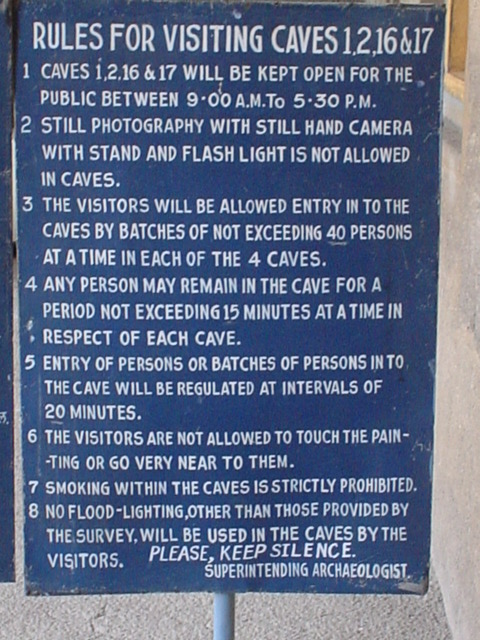

Rules for cave visiting at Ajanta |

A Jain Cave at Ellora |

Anyway, back to Elephanta Cave... The cave is about 130 square metres in floor area, as I said, fairly large! As noted above, it is supported by rows of massive pillars that rest on square bases and have fluted shafts with bulging cushion capitals. It looks like they were 'put there' so to speak, until you realise that they were carved out of the solid rock, as with the rest of the cave. They have absolutely no roof supporting function at all.

The temple faces North, where one enters through a porch, and there are two other porches to the East and West, both of them leading to the courtyards with subsidiary shrines. The great sculptured panels, the principal glory of Elephanta, are at either side of these porches. And yes, they are stunning, particularly one of the god Shiva.

Near the entry to the cave is relatively small museum, with a sour-looking (they all were ...) security guard seemingly barring the entrance - which probably accounted for the lack of visitors inside. Undaunted I bounded up and entered, and the guard and I spent a wary half an hour alone with each other. And the museum (more world heritage money again, I guess) was extremely good - well laid out, with excellent panels and interpretation (infinitely better, and that's being kind, to the Prince of Wales Museum in Bombay).

Of course, I wished to take photos - upon obviously preparing to do which my security 'friend' pounced. Not permissible (which is not unusual inside any building in India where one would like to take a photo...). However, having been in India some weeks, I was by now well aware of 'how things works'. My sudden production of a fifty rupee note instantly made my adversary a friend indeed, and I thus merrily proceeded to take the desired photos.

Management Issues

For all the difficulties presented by the sites themselves, and the fact that they are in India (which, as a country, works, but not always well ...), the rock-cut caves of Western India I visited, by and large, appeared to me to be quite well managed. These are under the overall control of the Archeological Survey of India (a Government of India statutory body), and a 'Superintending Archeologist' heads each site. At Ajanta, there are a number of appropriate restrictions on visitation to the four caves containing the wealth of murals (see opposite).

These caves are air conditioned, have restricted group sizes and a group "in cave" time of fifteen minutes, and have excellent subdued lighting. In addition, 'chemical restoration' (sounds doubtful, but I am sure it's kosher) is happening in the sensitive caves, and each has scaffolded sections with 'chemical restoration in progress' signs dangling from them.

At Ellora, largely without murals, this problem is not such an issue. Managing carved basalt rock faces largely amounts to keeping the tourists hands in their pockets, and there are plenty of security people around to assist. Fortunately, except perhaps for Kanheri, the caves are far enough away from large cities to make air pollution a non-issue.

|

|

|

An interesting sign at Ajanta Caves |

Bat screens under construction at Ellora |

Crystals in a basalt fracture at Ajanta |

One issue at Ellora that I noted was an obvious bat 'problem'. As they would, our little friends have, doubtlessly for hundreds of years, found the caves ideal habitats. I did note guano, though far from thick, in several caves, and I suspect staff regularly cleans up after the event, so to speak. The answer in several caves at Ellora has been to 'gate' them with wire mess grills, preventing bats access at least to the back sections of many. Well, good for the caves perhaps, but necessarily for the bats. How endangered or otherwise the local species are, I have no idea - but probably it is a case of the collision of two conservation issues, with the bats getting the rough end of the stick.

Another matter caught my attention even before my cave visits. At various markets around India there was always at least one stall (often more) selling 'cave crystals' - which in most cases looked like deposited calcite. Intrigued, I enquired, to be advised they came from Ajanta! As I already knew Ajanta was in basalt, I was further intrigued! Upon arriving at Ajanta, it quickly became obvious that the basalt was very often fractured, and in those fractures usually appeared the said crystal deposits. Not being a geologist, I will not speculate, but I am sure somebody will soon inform me of the processes involved!

The Ajanta basalt does extend over a very wide area well beyond the caves, from where doubtlessly the crystals are mined, to be subsequently flogged to tourists all over India. I also noted some rock fracturing and crystallization at Ellora, but not to the same extent as at Ajanta. In any case, Ellora is a relatively small volcanic area and wholly protected, unlike the far wider geographic area of the Ajanta basalts.

So to conclude - without doubt, the rock-cut caves of Western India are a world treasure, and both wondrous and staggering, to say the least. Happily, they also seem to be well managed. I would most certainly urge anyone traveling to India, whether cave-interested or not, to visit at least Ajanta and Ellora ... but don't tell the security guards that Kent sent you ...!