The Azores Archipelago comprises nine major islands dotted across about 600km of the Atlantic, 1600km west of Portugal, of which it is a province. All the islands are volcanic, like the Canaries and Hawaii. Unlike those more equatorial chains, the Azores has not been spoilt by tourism; in fact I found it impossible to buy a tourist guidebook to the Azores - some of those on Portugal barely mention the islands. What they may lack in weather and beaches, they more than compensate for in their volcanic landforms - above and below ground.

The town of Madalena at the western end of the central island of Pico was the venue for the 11th International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology and meeting of IUS' Commission on Volcanic Caves, held 12-17 May 2004. Over 40 people attended, about half of them from the islands or the mainland. 14 countries were represented. The meeting was organised by a group of local bureaucrats (the islands' Department of Environment), academics and speleologists, supported by the Regional Assembly, Departments of Culture and of Tourism, every municipal government, environment groups, museums, schools, cavers, etc. Considering the small population (the islands total 244,000; Pico, second largest, has less than 15,000), the event was remarkably well organised. If there was one general complaint it was the cost of accommodation. The hotel was expensive; the cheaper option was billeting in private homes, which was ... expensive.

The Symposium

A number of the papers presented at the symposium related to cave management. One covered the generally poor state of geological heritage ('património geológico) protection in Portugal but suggested the islands were ahead of the mainland. One listed the top ten volcanic caves in the world on the basis of cave minerals - and Victoria's Skipton Lava Cave gained a place (on the basis of new cave phosphates described from it in 1997). There was a presentation on the "Centro interpretação subterrâneo da Gruta Algar do Pena" in a park in mainland Portugal and another on environmental education at the Gruta do Carvão (São Miguel I., Azores) - some 1440 students have been conducted through this cave which runs under the main town, Ponta Delgada (Braga 2004). A group of academics, managers and cavers have set up a database of Azorean caves and within that they have assigned scores to each of the 86 listed caves on the basis of their scientific value, potential for tourism, access, surrounding threats, available information and conservation status. These scores are then weighted, depending on their biological components, geological features, accessibility, singularity and beauty, safety, 'caving progress', threats, integrity and available information. From all this they have ranked their caves in terms of scientific value, tourist potential and conservation (Constância et al. 2004). It was not clear whether these assessments have had any practical impact on management.

A project to build a visitor centre at Gruta das Torres, Pico, the longest cave of the islands (over 5.2km) and open 400m of the cave to visitors, was outlined. I admit to not having been impressed by the planned construction of "a stone wall 1.8m high to surround the skylight entrance and at the same time to allow the drawing of the building to emerge from it" (Vieira da Silva & Vieira 2004). Any construction so close to a cave is likely to have significant physical and aesthetic, and possibly biological, impacts on the cave. My expressions of concern were dismissed but, having later visited the cave, I remain sceptical as to the wisdom of the plan.

Studies of Azorean caves sought to assess their conservation values on the basis of arthropod fauna and bryophyte flora of entrances. The high invertebrate diversity of four small lava caves on Madeira Island was described, with a call for protective measures. Potential volcanic and pseudokarstic features for inclusion in a World Heritage nomination from Jeju Island, Korea, were outlined (by ACKMA member Kyung Sik Woo).

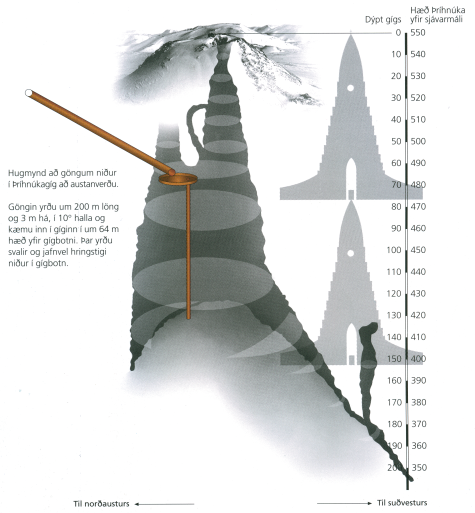

Perhaps the most unusual presentation of the symposium was by Icelander Árni Stefánsson (2004) on the feasibility of providing public access to the volcanic conduit Thríhnúkagígur, in mountains not far from Reykjavík (The 'Th' should be an Icelandic letter like a modified 'P' but its sound is 'th' - which doesn't help much as the rest is virtually unpronounceable).

Since exploring this 200m deep drained volcanic vent in 1991, Árni has been trying to work out how to open it to tourists. He considered a tunnel to the bottom but rejected this as the view up is 'impressive but not attractive' and there is the danger of falling rock. A spiral stairway from the top he also rejected as it would damage notable lava formations in the narrow shaft and it would spoil the impressive view up to the mouth. It would also need to be 65m long to show the best parts of the vault. So he has now come up with an idea to drill a 200m inclined shaft opening into the vent about 60m below the mouth (Fig. 1). A circular balcony would then be constructed on top of a single support rising 56m from the rubble pile on the floor; this would give a good view of the best features and could be positioned to avoid falling rock and snow. The view down would be 'like standing on top of a 20-storey building inside a mountain'. Local authorities have shown interest but engineering feasibility studies have not been conducted; local cavers are apparently less than enthusiastic.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Section through the volcanic conduit, Thríhnúkagígur. The silhouette is of a large church in Reykjavík which is ~80m high. [from Stefánsson 2004b] |

Fig. 2. Entrance pit with stone steps, Gruta das Torres |

Fig. 3. Symposium participants visit Gruta das Torres |

There were a number of other speleological, biological and geological technical presentations on aspects of volcanic caves and pseudokarst from Iceland to Hawaii, via Hungary, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Japan, New Mexico and Costa Rica. The meeting approved a concluding statement, recommending:

- National and international institutions need to recognise the importance of the geological heritage, especially volcanic caves;

- In volcanic regions vulcanospeleological heritage should be considered a key factor in economic development;

- Studies in volcanic cavities should be supported, particularly in relation to mineralogy and cave microbiology;

- Monitoring and identifying environmental indicators are very important in volcanic cavities;

- Balance should be achieved between tourist activities and conservation of vulcanospeleological heritage;

- A database should be created covering the 100 most important volcanic caves;

- Field work should be promoted in Azores volcanic caves, especially in the fields of biospeleology, mineralogy, microbiology and vulcanospeleology;

- A comprehensive management plan should be prepared for conservation of the volcanic caves of the Azores;

- Special conservation management measures should be applied to the highest priority volcanic cavities of the Azores, as identified by GESPEA.

Hopefully the proceedings will be available soon.

Faial and Pico excursions

On Faial Island an excursion visited Ponta dos Capelinhos where a series of eruptions in 1957 added a large area of land and burned a lighthouse. A small museum nearby has excellent interpretive displays on the eruptions and their effects. A visit was made to the Gruta do Capelo and the spectacular Faial Caldera which is accessed by a tunnel drilled through the side of the volcano. The caldera is 400m deep and 2km across. There is on-site interpretation.

On Pico the first cave visited was Gruta das Torres, as mentioned above, the longest lava tube cave in the Azores (5.2km). It is one of few caves formally reserved in a Regional Natural Monument and is to be developed by the Regional Department of Environment. So far the only infrastructure consists of some very solid stone steps in the entrance pit (Fig. 2) but further into the cave "an overpass 40m long will allow visitors to avoid existing breakdowns, without the need to remove debris" (Vieira da Silva & Vieira 2004). Tours are planned to run 200m in either direction from the entrance. Helmets and electric torches will be provided after visitors receive a 'briefing' in the planned visitor centre. A booklet has been printed. The cave is quite spacious (Fig. 3) and has most of the usual lava cave features such as lava 'stalactites', flow structures and roof breakdown.

The second cave visited was Gruta dos Montanheiros. This was accessed down a long, fixed aluminium ladder, lying on top of a rotting wooden one (Fig. 4); clearly access to this cave has been provided for many years but there is no evidence of active management. The most striking elements were some very colourful flow features. Gruta do Soldão was also visited. Its most striking features were a cold puka (a daylight hole that had clearly collapsed after the tube had cooled) and its downflow termination in a sea cliff.

Five delegates climbed the very prominent Mount Pico volcano, highest mountain in Portugal, at 2351m. As the starting point is at 1200m it is not a particularly difficult ascent. There are a few interpretive signs and the trail is marked by guideposts; nevertheless, we engaged a local guide. Highlights were a couple of impressive hornitos and the steaming fumarole at the top which warmed us while we ate lunch. Heavy cloud prevented us seeing what must otherwise be impressive views.

Post-symposium field trip

A field trip after the Symposium took us to São Miguel, Terceira and Graciosa islands. On São Miguel we saw only one cave, Gruta do Carvão, which runs under the major town, Ponta Delgada.

The cave is well suited to 'adventure tours' and part is illuminated with electric lights. A local environment group, Amigos dos Açores Ecological Association, has been conducting visits by local students since 1998. The cave has some very fine displays of 'lava cave slime' which were pointed out to us by Dr Diana Northup (a veteran of Lechuguilla) (Fig. 5). The following day we visited hot springs, fumarole fields (at one of which our lunch was cooked in a hole in the ground), crater lakes, boiling mud pools and a geothermal power station.

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Temporary access to Gruta dos Montanheiros |

Fig. 5. Dr Diana Northup points out cave slime on lava 'stalactites', Gruta do Carvão |

Fig. 6. Concrete and ceramic-lined canals collect water in Furna d'Agua, Terceira |

On Terceira we were looked after by members of Os Montanheiros, the local caving group (inappropriately? named "The Mountaineers", but with the explanatory 'subtitle' Sociedade de Exploração Espeleológica) which runs the island's two show caves.

First we paid a visit to Furna d'Agua, a cave which provides a portion of the local water supply. Water flowing into the cave is captured by a canal system (Fig. 6) and carried to a surface reservoir. Limited public access is apparently permitted but this is hardly your standard show cave. Not far away is Furna do Cabrito (Goat Cave) which has been even more heavily engineered.

On the surface its entrance is marked by a concrete dome (probably to keep the goats out) about 10m in diameter with a telephone box-sized portal on top (Fig. 7). Under the dome the original collapse entrance is pretty well preserved but through it descends a huge concrete circular stair structure which would do any show cave proud (Fig. 8).

In this case, though, it only provides access to more water-works. About 50m upflow of the stairs the 8m high cave has been sealed with a concrete wall, creating an underground dam.

Next we were off to the real show cave, and one of the highlights of the visit: Algar do Carvão. The turn-off is marked by a most distinctive sign and 'sculpture' (Fig. 9). This cave was given to the Os Montanheiros group a few years ago and it has successfully developed and operated it as a show cave since 1968. Electric lighting was installed in 1970. The shaft was first entered in 1893 but the cave was not fully explored until 1963 (Costa 2002).

|

|

|

Fig. 7. The domed concrete structure over Furna do Cabrito |

Fig. 8. Spiral staircase into Furna do Cabrito |

Fig. 9. No one misses the turn-off to Algar do Carvão! |

This is a truly extraordinary (probably unique) and spectacular cave, the layout of which is best described by a section (Fig. 10). It is comprised of a vertical element about 50m deep, a volcanic conduit 15-20m in diameter, formed in basalt which broke through the horizontal element - a large cavern in trachyte which extends down another 40m, ending in a clear (seasonal) lake. The walls of the trachyte chamber are heavily encrusted with amazing speleothems of amorphous silica and limonite which mimic their calcite counterparts in karst caves (Fig. 11a, b, c).

Apparently the stalactites and flowstones are formed by deposition of soluble silica and iron minerals; the limonite forms by oxidation. Black obsidian provides a contrast on the walls. Originally access was by rope; later a 'flying-fox' was built, but eventually, "during their weekends and holidays" The Mountaineers dug a 44m tunnel (later enlarged and strengthened by cement) through to the vertical conduit (Os Montanheiros n.d.). Inside the volcanic chimney they initially built a wooden staircase down to the trachyte chamber but this has been replaced by a steep zigzag path (Fig. 12). The path then winds around the huge chamber with the speleothems on its walls (Fig. 11a), eventually descending and ending at the edge of the lake. The water is crystal clear but looks green under the installed lighting (Fig. 14).

This remarkable cave is a Regional Natural Monument, due to its volcanic features (Forjaz et al. 2004); it rated #1 in Paolo Forti's list of volcanic caves based on minerals, for "best and largest display of opal speleothems" (Forti 2004); it contains its own fauna including an endemic cave beetle, Trechus terceiranus, and two endemic cave spiders (Os Montanheiros n.d.); it probably merits World Heritage listing.

The size of the entry shaft and the main chamber provide real challenges for photography and one needs to make a few circuits of the track to take everything in. The entrance building contains interesting photos and displays, plus a basic kiosk selling postcards; there is a small brochure on the cave (Os Montanheiros n.d.).

|

|

|

Fig. 11a, b, c. The walls and ceiling of the big trachyte chamber are festooned with 'amorphous silica' (opal) speleothems; there is no calcite in this cave! |

||

|

|

|

Fig. 10. Section through Algar do Carvão [from Os Montanheiros n.d.] (dimensions are in metres) |

Fig. 12. A zigzag path descends the basaltic chimney to the big trachyte chamber |

Fig. 14. The lake at the lowest point of Algar do Carvão fluctuates seasonally |

That evening we visited the headquarters of the Os Montanheiros group in Angra do Heroismo. This 4-storey stone building is probably the finest 'clubhouse' of any local caving group anywhere. One floor is devoted to reception, office and meeting room, another to a geological and natural history museum, another to historical displays, topped off with a large library, map cabinets, computers and archives. The symposium participants were astonished that such a place existed, evidently the result of a very hard-working, dedicated group over many years, backed by the income from two show caves! We visited their other cave the next day on our way to the airport. It is a fairly ordinary lava cave called Gruta da Natal (Fig. 15); something of an anticlimax after the spectacular Algar do Carvão.

We flew to the small island of Graciosa and next day toured the island's features by minibus. We drove part way up the main volcano and then through a tunnel giving access to its caldera.

From a carpark we walked down to the large opening to a cave at the lowest part of the caldera - the Furna do Enxofre (Sulphur Cavern).

While we waited for the guide to unlock the door, we could see down the entry shaft (Fig. 16) from which arose the sound of a siren which we were told indicated excessive foul air in the lowest part of the cave. Once through the door we climbed down the long spiral staircase to a huge single cavern, 194m long and 40m high (Costa 2002) terminating in a lake (Figs 17, 18). The stone access tower, built early in 20th century, is a striking feature of the cave; it is 37m high (Fig. 19).

|

|

|

|

Fig. 15 Typical lava tube passage, Gruta da Natal |

Fig. 16. The gaping maw of Furna do Enxofre |

Fig. 17. Part of Furna do Enxofre's 'big room' |

Fig. 19. The stone entry tower extends down the volcanic vent of Furna do Enxofre |

At the back of the big room was the only fumarole to be seen in an Azorean cave (Fig. 20). Presumably it is the source of the foul air. We felt no ill-effects from foul air but apparently the alarm system had been installed because a few years ago two men had dived into the lake and on surfacing had died from lack of oxygen immediately above the water.

This impressive cave is operated by the local municipality. The only interpretation is a photocopied note sheet in Portuguese, English, French and German. A plaque commemorates a visit by a Prince Albert of Monaco, but doesn't mention the date (apparently it was about 1879 when the 40m shaft had to be descended on a rope ladder).

We flew back to Terceira that evening, ending what had been a most interesting and enjoyable symposium and associated excursions.

|

|

Fig. 18. The lake in Furna do Enxofre - being photographed by a photographer from National Geographic. The foul air detector is just visible at lower right |

Fig. 20. Part of Furna do Enxofre's fumarole; steam and gases bubble up from under breakdown |

REFERENCES

BRAGA, Teófilo 2004 Gruta do Carvão in the island of S. Miguel (Azores) and environmental education. Abstracts, XIth International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology, Pico Island, May 2004, p. 21.

CONSTÃNCIA, J.P., BORGES, P.A.V., COSTA, M.P., NUNES, J.C., BARCELOS, P., PEREIRA, F., BRAGA, T. 2004 Ranking Azorean caves base[d] on management indices. Abstracts, XIth International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology, Pico Island, May 2004, p. 22-23.

COSTA, Paulino (ed.) 2002 Azores volcanic caves. Direcção Regional do Ambiente e Gespea: Azores, Portugal. 32 pp.

FORJAZ, Victor H., NUNES, João C., BARCELOS, Paulo 2004 Algar do Carvão volcanic pit, Terceira Island (Azores): geology and volcanology. Abstracts, XIth International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology, Pico Island, May 2004, p. 24.

FORTI, Paolo 2004 Genetic processes of cave minerals in volcanic environments: an overview. Abstracts, XIth International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology, Pico Island, May 2004, pp. 12-13. Full paper since published in Journal of Cave & Karst Studies, April 2005, 67(1): 3-13.

OS MONTANHEIROS n.d. Algar do Carvão: a unique volcanic landscape. Brochure published by Os Montanheiros, Terceira, Azores. 8 pp.

STEFÁNSSON, Árni B. 2004a Feasibility of public access to Thríhnúkagígur. Abstracts, XIth International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology, Pico Island, May 2004, p. 59.

STEFÁNSSON, Árni B. 2004b Thríhnúkagígur. A colour booklet (in Icelandic) promoting the opening of this volcanic shaft. 8 pp.

VIEIRA DA SILVA, Inês & VIEIRA, Miguel 2004 The project for the visitors centre building of the Gruta das Torres volcanic cave, Pico Island, Azores. Abstracts, XIth International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology, Pico Island, May 2004, pp. 25-26.