Imagine Mike Munro walking into

Abracurrie on our next trip to the Nullarbor and uttering these words -

ALloyd Robinson, This is your

Life!@

Well,

permission has been granted by Peter Ackroyd and Lloyd Robinson (as co-authors)

to reproduce this article in the ISS Newsletter from VSA=s >NARGUN= Vol. 22 no.10 . A few paragraphs by Dave Dicker

fill a couple of holes within the article that provide a story to match any of

those Australians who have appeared on AThis is your Life@.

Enjoy

reading and being mesmerised by Lloyd=s adventures and in caving.

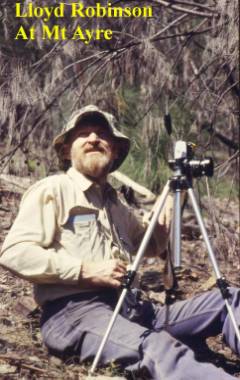

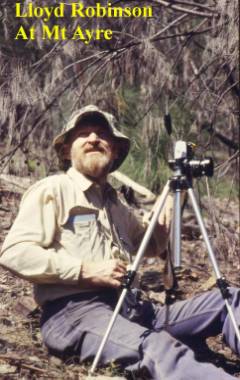

Lloyd scanning the karst in the Northern Territory – taken by Pru

Wellington from New Zealand

Forward by Peter Ackroyd

Like

you, I am impressed with Lloyd's exploits and would encourage modern cavers to

learn more about the achievements of our caving pioneers. This was my intention

when I first asked Lloyd to give the talk to VSA in September 1989 and I taped

it (with Lloyd's permission of course) for later editing and publication in

Nargun.

Summary of

a talk presented to the Victorian Speleological Association by ASF President,

Lloyd Robinson on 6th September 1989

Some Post War memories of Caving and Expeditioning in Australia

by Peter

Ackroyd and Lloyd Robinson

Introduction

Lloyd

Robinson was born in Alstonville, northern NSW, in late 1927, son of a dairy farmer

who had been in trench warfare and gas attacks in WW1. In December 1936, Lloyd=s father, advised by doctors to move

to a cooler climate, bought a general store at Marulan near Goulburn, NSW.

Growing up

in the country meant that Lloyd learnt to shoot, ride, swim and generally make

the bush his home. The nearby Bungonia Caves to the south of Marulan provided

Lloyd with his first caving experience - visiting Grill Cave [B-44] at

about 12, using candles and a reel of cotton.

In December

1942, with World War 2 seemingly set to go on forever, the family moved to

Wollongong, NSW. Lloyd, like most other youths, looked forward to the day that

he turned 18 and could join up. Lloyd=s father, however, knowing the horrors of war,

took him to Mt Keira Colliery for an interview and subsequent apprenticeship.

Coal mining was classified as an essential service and no coal miner was

permitted to join the armed forces. Whether Lloyd=s father planned this or not became

irrelevant - the war ended just before Lloyd=s 18th Birthday.

Early

influences

Entering

the Wollongong workforce from Aoutside@ was not easy. Union pressures were strong and the region had suffered

many serious underground methane explosions resulting in much loss of life,

causing the workers to close ranks. Consequently, Lloyd and his brother visited

their old friends at Marulan, taking their bicycles to MossVale on the train,

then, riding to Marulan. It was not uncommon for trips to be made to Bungonia

Caves by bicycle from Marulan.

At the end

of the war an ex-commando returned to his old job at Mt Keira Colliery. He had

been a member of the 2/2 Commandoes, Sparrow Force, which had fought behind

Japanese lines for two years in East Timor. The commando=s tales of the extensive caves in

East Timor, used to the Australian=s advantage in their guerrilla campaign against

the Japanese, appealed to the colliery apprentices greatly. However with

restricted transport, low wages, few holidays and school three nights a week,

there was little that could be done to take the interest further except for

occasional trips to tourist caves. Nevertheless, the seeds of an explorer of

caves in far off places were sown, to await germination.

The

first trips

The chance

came in the late 1940s when hard earned wages were spent on motorbikes. Petrol

rationing would remain in force until almost 1950 but, despite this, trips

ranged far a field to caving areas known only from sketch maps produced by

Paddy Pallin (Colong, Tuglow) or, in one case, from an old Shell road map (Big

Hole).

Information

was very scarce! Some cave locations, taken for granted today, had become >lost=. The massive disruption caused by

the population shifts during the depression, then the loss of many thousands of

young country people during the Second World War, meant that oral histories had

become disjointed, or lost altogether. Sydney=s Mitchell Library was in disarray

and the lifting of the wartime controls was slow, resulting in much of the

information needed to relocate caves and air photos we know today simply did

not exist in the late 1940's and early 1950s.

So with

increased mobility, a yearning to explore caves but limited knowledge of

locations, an early aim became the bottoming of the 150 feet first pitch in Drum

Cave, Bungonia. Everything had to be able to be carried on motorbikes.

Moreover, petrol rationing forced the apprentices to supplement their fuel with

paraffin oil and kerosene. These fuels were not effective until the machine was

warmed up on petrol, and even then, only when travelling at more than 50 miles

an hour (80 kmph). The use of such fuels also caused early reboring of the

motor.

No-one in

Australia made lightweight ladders that could be transported easily by motor

bike, so a letter was sent to France to enquire about the manufacture of >electron= ladders. When the plans came, the

light 3mm wire and half metre spacings of the rungs were viewed with alarm by

the Colliery=s rope splicers - Aonly fit for clothesline!@. They convinced the budding cavers to use 3/16

(5mm) galvanised wire and rung spacings of 15 inches (380mm), later reduced to

12 inches (300mm). Rungs were cut from >Durallium= - warplane aluminium tubing. Two

ladders of 55 feet each were constructed. These did not reach [the bottom of

Drum], so further lengths, of a more manageable 30 feet were constructed. When

the cave was finally bottomed, it was a disappointment - it didn=t go.

The

neophyte cavers formed a loose group called the Wollongong Speleological

Society to give them some standing when approaching landowners, and to help in

dealing with the police. Travelling groups of young men were not common then,

and were viewed with suspicion by the local gendarmes.

Using Paddy

Pallin's maps, a party of six canoed the Wollondilly River in the early 1950s

(before the construction of the Warragamba Dam), stopping to trek overland to

the Colong Caves ‑ the best wild caves they'd yet seen.

The Big

Hole [I5P-2]

After the ending

of petrol rationing in 1950, the small group, ranged further afield, often only

two people, on one bike. Information was still scarce and many times they would

follow up farmer=s glowing reports of huge caves only to find a shallow depression or a sandstone

overhang.

The Big

Hole is a classic case of a major feature >lost= to the then present

generation. It was first noted because

it appeared on a Shell road map belonging to one of the group. Enquiries to

Shell=s mapping section drew a blank ‑ they simply put it there on older

maps because there was an empty region on the map at that point. No road led to it and they had no

information about it. Some enquires the group made at Braidwood mainly

regarding access to the Shoalhaven River for a canoe trip to Nowra, did turn up

one clue. A few farmers confirmed that a substantial hole was reported to exist

somewhere to the South.

Later on in

1954, with a few holidays to spare, Lloyd accompanied by the late Russell

Badans made a reconnaissance trip south of Braidwood in search of the elusive

hole. They called in at each farmhouse beyond the Ballalaba Bridge. One lady, in response to their enquiry, said

that, if her son had returned from the War, he could have taken them straight

to the Big Hole a poignant reminder of the loss of life in the War. At Krawaree they were told to try 82

year-old Mr Hindmarsh, just the other side of the Shoalhaven River. Mr

Hindmarsh lived alone in his small house still able to look after himself, and

keen to take the boys to the Hole if he=d been younger. However, he was able

to give a fair bit of detail about the Big Hole.

Originally,

about 1880, the hole had been smaller at the top, the sides undercut and it had

a small stream flowing across the bottom. As a boy he [Mr Hindmarsh] had

watched his father and others cut trees from around the rim so they could watch

them crash and splinter to the bottom. After all the trees had been felled in

this way the sides began crumbling and the edges migrated back to the next line

of trees. The rubble piled at the bottom and covered the stream up. The Big

Hole had been descended in his day by using a miner’s windlass and a bucket

made of a 44 gallon drum. Getting people in and out safely at the top was

difficult - some people yelled to be hauled back up as soon as they started to

descend. Once, the Big Hole was used

as a prop for a mining swindle. Prospective investors were shown the hole and

even lowered down it if they wished.

Mr

Hindmarsh did not believe that anyone had been down the hole after the turn of

the century and that there was now little interest in it. He reckoned it to be

300 feet deep. He pointed out where the whole was from his verandah, gave them

some rough directions then left the two young explorers to it.

Lloyd and

Russell took their bike as far as they could to a campsite then set out to

cover the hill shown to them on foot. They criss-crossed the side of the hill

Mr Hindmarsh had told them to go, but to no avail. Eventually, tired and disgruntled

they went to the top of the hill to take a photo - using the still hard to come

by Kodachrome colour film. Upon taking

the photo the pair headed down to the campsite in the twilight and almost fell

down a enormous hole. It would have been easy to walk straight into it. The next morning they took photos of the Big

Hole and headed back to Wollongong.

During a later visit a partial descent was made to enable the depth to

be accurately plumbed so that the correct length of ladder could be manufactured.

The Big Hole was then descended.

The

major expeditions

The three

Potts brothers and the two Robinson brothers were the main driving force in the

early 1950's. They went on long hikes, built their own canoes and canoed all

the nearby rivers. In June 1955 Bob

Potts and Lloyd went halves in a short wheelbase, softtop Landrover. They

overhauled it with enthusiasm then in July 1955 set of in search of Lassiters

Gold Reef ‑ the long way.

First they

went to Brisbane, then west to Roma where they first learnt about black soil

plains. Upon arriving in Mt Isa, they realised that an increase in funds was

necessary, so it was back to work in the mines for a month. During this stay,

each weekend was spent at Camooweal Caves with the (now defunct) Mt Isa Speleological

Club. Lloyd was impressed at the speed these lads could open up the caves at

Camooweal using explosives, readily available from the mine.

From Mt Isa

the pair travelled out to Ayers Rock, then beyond. The locals told them that

they were the fifth vehicle ever out there. After some time in the desert, they

returned to Adelaide, then home.

The next

trip was to be via canoes that they had built themselves. They took the train

to Albury, their canoes in the guard's van, then hired a truck to take them to

just below the Hume Weir. They put

into the Murray River in October 1955 in one of the highest river levels

recorded and paddled downstream for almost three months. At one point, below

Mildura, they found themselves 40 miles inland, according to the map. They were

feted at many of the major towns ‑ no one had done anything like this

before. They reached the ocean at Goolwa on 6th January 1956. They'd covered

more than 1,400 miles. A Landrover needing an overhaul and no money meant it

was back to work in 1956. In May 1956, Lloyd suffered a serious electrical burn

which hospitalised him for several months and left him with a disabled right

hand. Bob Potts got married. Activities

declined somewhat during the year. After convalescing, Lloyd bought out Bob's

share of the Landrover, overhauled it and in October 1957 set out for Western

Australia with Bert Broadhead, a 'survivor' of the original group, both were

foundation members of the Wollongong Speleological and Expeditionary Group.

The Western Australia Years

The Western Australia Years

Between

October 1957 and mid 1958 Lloyd was in Western Australia examining the caves of

the Nullarbor, Jurien Bay and exploring Augusta Jewel Cave, Easter

Cave and other major WA caves.

Augusta

Jewel Cave [AU‑13]

is Western Australia=s most famous cave and when Lloyd, accompanied by Cliff Spackman and Lex

Bastian, explored it and realised its great significance they were in a

quandary. How could it be protected? They consulted the late Bill Ellis who

referred them to the local Member, Stewart Bovell, later Sir Stewart. They were

advised to make a splash ‑ newspaper coverage, special tours, letters to

the Government, anything to ensure that its significance was recognized by the

people in power.

The latter

part of 1958 was spent back in Wollongong as a member of the Wollongong City

Fire Brigade waiting for the granting of the contract for Cliff Spackman and

Lloyd to prepare the Augusta Jewel Cave for tourism.

In December

1958 Lloyd returned to WA to start the development of Jewel Cave with

Cliff Spackman. Lloyd, Cliff and Lex Bastian approached the status of

celebrities because of their discovery, and for a few months Lloyd was a face

recognized in the crowd. However this soon passed, but the lasting effect of

the trio=s actions was that the Jewel Cave was spared the degradation that

the once fabulously decorated Moondyne Cave [AU‑11] had suffered.

Ever on the

lookout for new ways to discover caves, Lloyd became interested in the

geologists' seismic surveys. These employed an explosive charge placed in a

central location, and a grid pattern of geophones set out to pick up the

'reflections' from the blast. These signals could be interpreted to help locate

ore bodies. While blasting the entrance

to the Jewel Cave in 1959, Lloyd set out geophones and, with a simple

set of earphones, learned to differentiate between solid limestone and known

caverns. He then started setting the

geophones in other areas and in this way the main caverns of The Labyrinth

[AU‑ l6] were pinpointed.

Some months

of searching were to pass however, before they stumbled onto the strongly

draughting, but otherwise insignificant entrance to the mile long cave.

AZUYTDORP@

Notes by

Dave Dicker

Also in

1958, Lloyd was invited to take part in Phil Playford=s expedition to identify and

investigate the wreck of the Dutch East Indian AZuytdorp@, which was wrecked off the West

Australian coast near Geraldton in 1712. Artefacts and other evidence collected

before and during the 1958 expedition, pointed conclusively that the wreck was

indeed that of the AZuytdorp@. Unfortunately, the rough seas did not permit the expedition divers to

investigate the wreck site itself at the time. Lloyd=s function on the expedition was to

investigate any caves in the vicinity for survivor occupation, (it was evident

that there were some survivors of the wreck) and well as looking after some

resupply logistics.

Reference:

Playford, P

The Wreck of the AZuytdorp@, 1958

Between

1960 and 1964, Lloyd spent 20% of his time in WA, and 80% in Wollongong, NSW.

The time in Wollongong was spent in the search for Bendethera caves. These were

[re]found by Lloyd and Jim Gould in

October 1960. Initially walking in, then using a very rough council track, with

grades reaching 420 in places, the crew battled their land rovers up

to the caves, the locations of which they=d discovered from ''Limestone

Deposits of NSW@. The Bendethera efflux was irresistible and digging commenced straight

away. Being miners, it was not too long before a petrol powered generator had

been hauled up to the cave in pieces, then reassembled. The mining operation

included the generator, drills, shoring, muck carts and plenty of bang. The dig

was finally abandoned in 1972 with a strong stream still pouring out of a, by

now, moderate cave.

(Dicker,

1979).

Wyanbene,

helium balloons and aven photography

Always

something of an inventor, and captivated by the towering 376 feet aven near the

far end of Wyanbene Cave [WY-1], Lloyd lead a group of Illawarra

Speleological Society cavers to explore it by remote methods. Using plastic

sheathing as supplied to dry cleaners, a cylinder of helium gas dragged labouriously in through the 3000 feet of stream passage in Wyanbene Cave, and

various bits of photography gear, Lloyd led several expeditions to this aven in

the early 1970's.

Up to three balloon 'sausages' about

12 feet long each, were sent up with their payload of batteries, camera and

flash unit on a very fine woven 0.15 mm thread. At first, a shutterless camera

was sent up consisting of nothing more than a lens, a black painted Balsa wood

box and a clip-on back to hold a single sheet of cut film. This apparatus was

sent aloft, the flash fired by remote means and then retrieved in complete

darkness ‑ a tricky manoeuvre. Despite the cost in terms of weight, a new

camera with a shutter was added, fitted with a solenoid to provide remote

control. A series of successful flights were undertaken with the whole balloon

at one stage drifting completely out of sight somewhere near the top of the

aven. Several photos, in black and white were taken, some aimed directly

downwards, which illustrated the immense height of the Gunbarrel aven.

Up to three balloon 'sausages' about

12 feet long each, were sent up with their payload of batteries, camera and

flash unit on a very fine woven 0.15 mm thread. At first, a shutterless camera

was sent up consisting of nothing more than a lens, a black painted Balsa wood

box and a clip-on back to hold a single sheet of cut film. This apparatus was

sent aloft, the flash fired by remote means and then retrieved in complete

darkness ‑ a tricky manoeuvre. Despite the cost in terms of weight, a new

camera with a shutter was added, fitted with a solenoid to provide remote

control. A series of successful flights were undertaken with the whole balloon

at one stage drifting completely out of sight somewhere near the top of the

aven. Several photos, in black and white were taken, some aimed directly

downwards, which illustrated the immense height of the Gunbarrel aven.

The

Kimberley Ranges

Lloyd's

first trip to the caves of the Kimberley Ranges, in WA, was in 1977. Lloyd,

along with David Dicker, has now participated in seven expeditions to the

Kimberleys spending most time on the surveying of Mimbi Cave. Lloyd's

most recent visit (1989) to the 13.5km long Mimbi Cave [KL‑5] was

distressing. Lloyd found that the 'enlightened society' had been there, with

their spray cans of paint.

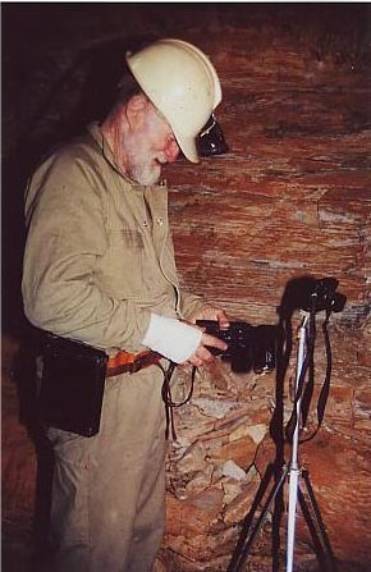

Lloyd

climbing an area in the Gregory Karst – taken by Pru Wellington from New

Zealand

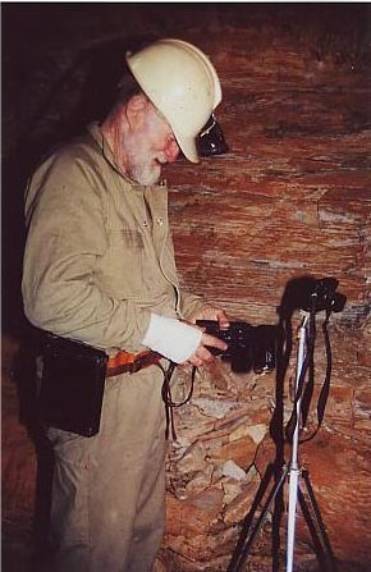

Photography

Lloyd setting up his new camera gear taken by Debbie

Hunter of Tasmania

In the

1940s, 64 ASA film was the normal black and white film to use; 125 ASA black

and white film was considered high speed. There were some faster but the

quality was poor.

The only

colour film was the hard to obtain Kodachrome with a film speed of 10 ASA. It

was only available in 20 exposure rolls. In 1945 Lloyd was able to obtain a

single roll of Kodachrome and it stayed in the camera for six months before it

was exposed.

For cave

and cavern photos the only lighting that could be considered for colour film

was Phillips PF100 blue flash bulbs. These globes cost one quarter of a week's

wage each and in the main, one had to go to Sydney to purchase them in small

lots.

A cave

shot, using the 'expensive' globe, involved some planning to avoid failure.

Bungonia was the only place Lloyd could reach with petrol rationing so this is

where all the early cave photos were taken. Saturday night was reserved for the

one or two cave photos that would be taken on a weekend trip. It was not

uncommon for a bulb to explode when fired ‑ an expensive failure.

Lloyd's

inventions

Apart from

the aven photography equipment manufactured for Wyanbene Cave, Lloyd has

been a prolific inventor. The 'sump snooper' was invented following his visit

to the still pools of Camooweal caves. The device would submerge, go into a

sump, be instructed to come up at intervals and, if in air, take a photo; if

not, resubmerge, go further and try again, and then to return. Unfortunately,

despite a huge effort to get it to the working stage, it was never used in a

cave and

the sump snooper still, as far as he is aware resides beneath his late parents'

house in Wollongong.

Despite

being invented by members of the Cave Exploration Group of South Australia, the

Diprotodon is a device synonymous with the name of Lloyd Robinson. First

invented by the eccentric caver, the late Captain J Maitland Thomson, refined

and miniaturized by the late Alan Hill and then brought to the pinnacle of

effectiveness and ease of operation by Lloyd, it was based on an essentially

simple principle. Granulated magnesium burns with a white light of such

intensity as to enable photographs to be taken of the largest of underground

caverns.

Captain

Thomson's device was based on a cumbersome, manually pressurized portable fire

extinguisher. Partially filled with magnesium powder, it was pumped up the

valve opened and the resulting stream of magnesium directed over a carbide

flame. It was smoky, hard to control and possibly dangerous but some fine

photos of Nullarbor caves resulted from its use.

Alan Hill,

of the Cave Exploration Group of South Australia had access to a large supply

of finely divided magnesium powder possibly originating from the Woomera

Project. The grains of this powder had a very low angle of repose ‑ they

flowed quite readily. A "Brasso" can fitted with an old style motor

cycle petrol valve was fitted with the powder, the pressure was supplied by a

large balloon blown up in the cave and a protective shield was placed around

the nozzle. The air valve was opened, the can was inverted, the air took

magnesium granules out to the nozzle where a carbide flame ignited the stream.

More photos of the Nullarbor's largest chambers resulted.

Lloyd took

Alan Hill's basic plans from the 1966 CEGSA occasional paper No 4 and added

refinements to provide a fully controllable high intensity, even, white

photographic light. To improve the 'pick‑up' of magnesium by the airflow,

an air relief valve was built into the base of the can to ensure a steady

stream eliminating the 'fluter' experienced by earlier users which made their

devices difficult for movie work (see footnote).

Lloyd's description of the operation is

interesting.

AFirst lay out all the components; the Brasso can should be full of

magnesium. Blow up a large balloon and slip it over the air intake nozzle with

the airflow valve turned off. If using the largest orifice, giving the maximum

flow rate, fit the extender tube then slip the 'reflector' over this. The

reflector is not really for focussing the light, its purpose is to protect the

operator. Mounted on the reflector (usually an old motor bike or car headlight

reflector) is a wire wrapped element. This is the heating element and consists

of both heavy gauge (1.8 mm) element

wire and fine gauge (0.5 mm) element wire. The small diameter wire has to be

replaced after every session. The distance this heating element is from the

nozzle is fairly critical. It should be about an inch or two, but final

adjustment is a mater of trial and error. Seven or eight weatherproof matches

(the kind which are half match head, half stick) are clustered around the

element in a holder provided. The operator puts on gloves and glasses or

goggles, lifts the Diprotodon with the Brasso can upright and lights the weatherproof

match cluster with a carbide light or another match. Once the matches begin to

heat the element, the air valve is turned on and the Brasso can inverted so the

magnesium flows into the mixing chamber and is picked up by the airflow. The

Diprotodon will >spit‑spit‑spit= for a second or two until enough heat is

generated and suddenly the whole chamber is bathed in brilliant white light.

One inexperienced operator has dropped the Diprotodon at this point‑the

event is so explosive. An experienced operator keeps calm opens the air relief

valve on the base of the Brasso can (which is now uppermost) and a steady white

light is generated for between 30 seconds and 3 minutes depending on the size

of the choke orifice fitted. This is enough time to get proper light readings

and good exposures of the chamber or features being photographed. The

Diprotodon can be set down for up to 10 or 15 minutes after the initial run and

still be hot enough to fire up straight away for the next photograph.@

Footnote:

My

Diprotodon is a copy of the late Alan Hill's version having seen his

demonstrated at the Mirboo ASF Conference (1966). I reasoned that it would be

less smoky if burnt at a higher temperature. To this end the following

additions were made:

a) improved

mixing chamber

b) modified

element structure

c)

separation of fuel into large & small magnesium granules

(plus low grade rubbish used for open air

demos).

I have also

made up a number of choke sizes for fuel saving in smaller caves or with

highspeed film.

These

modifications have made my unit burn hotter. The metal shield has to be rotated

during a burn or the top section would melt, despite it being made of mild

steel. Much later a modified air supply was added to eliminate the flutter in

light output - to help with movie work. It also had the effect of maintaining

consistent colour temperature for colour photography. ......LNR

In 1974

Lloyd was asked by the University of New South Wales Speleological Society to

accompany them to Kubla Khan Cave [MC‑I] in Tasmania so they could

employ the Diprotodon to light the Khan Chamber (Xanadu) for a movie they were

making. Lloyd advised them to have a trial run beforehand. However they did not

heed his advice and as a result the film was incorrectly exposed. Fortunately Andrew Pavey of UNSWSS managed

some well exposed still shots and UNSWSS were able to enlarge these, display

them on a screen then pan their movie camera over them to obtain their ''movie

film". (An example of Lloyd's photo of the Khan can be seen on the cover

of ASF Newsletter 64 ‑ taken after the discovery of the Khan and Xanadu

in 1966.)

Remote

Location Site Camera

Notes by

Dave Dicker

This

project was the result of a chance comment made on one of the earlier Kimberley

Expeditions. The culmination of the design effort came in 1991, when the camera

unit was installed in Mimbi Cave. The unit operated over a period of two years

without attention, giving satisfactory results. It was re-loaded and left for a

further year. Unfortunately, the vandals visited the site and redirected the

electronic flash, so no results were obtained on its third year. Astonishingly,

on recovery, the unit still operated after spending three years in an

unfriendly climate.

Although

the design and building of the project was a team effort, Lloyd was always the

driving force.

Reference:

ISS

Newsletters

Vol 3 Nos 6,7,8,9:

Vol 4

nos 1,2,4: Vol 5 no 1

This

summary really only scratches the surface of the vast pool of knowledge and

exploration history built up by people like Lloyd. Those who follow in their

footsteps, able to make use of modern equipment and techniques can only marvel

at what was achieved and urge Lloyd and his contemporaries to write it down

before it is lost forever.

Reference

DICKER,

David (Ed)(l979) Bendethera Edition ISS Newsletter 2 (2).

Recent

Developments

by Dave

Dicker

ASF:

Lloyd

was the ASF Safety Officer from 1966 to 1976, an ASF Vice President from mid 1977

to end 1978 and the ASF President for 7 years from January 1986 until the

January committee meeting in 1993. He is currently the Convenor of the Awards

Commission and always attends the biennial conferences and committee meetings.

Caving

Since

1989, Lloyd has been active on four Kimberley Expeditions, many significant

finds being made during this period. He has also made a further two low-key

visits, mainly to resolve the access problem.

He has

been active on three expeditions to the Nullarbor, and is preparing for a

fourth visit in 2003.

He has

been active on the CSS expeditions to the Gregory National Park, in the

Northern Territory over the last six years. He has been instrumental in finding

several new areas to survey, and also in joining up known caves. Dorothy has

been active in provisioning and general logistics for these expeditions.

Lloyd

has taken a lower profile as far as the local ISS trips are concerned. However,

he has encouraged several members in the art of cave photography and is still

enthusiastic in projects such as recording caves at Bendethera. In 1998, Lloyd

and Dorothy were made life members of ISS.

Return to the beginning

page of the Lloyd Robinson Story