Impounded Karsts of Eastern Australia

Background

An impounded karst (or "karst barré" or "contact karst") is a relatively small area of limestone that is completely surrounded by non-limestone rocks of low permeability so that much of its drainage and evolution is influenced by the external geology and hydrology.

Many of the Palaeozoic limestones of eastern Australia occur as long but narrow and steeply dipping outcrops (Jennings, 1967, 1976; etc - see readings list below). Many of these would qualify for the extreme case of "stripe karst", defined by Lauritzen (2001) as having a Length/Width ratio greater than 3, with its ideal development at L/W > 30. Stripe karst is distinguished by the overlap of the two contact zones from each side of the limestone belt so that allogenic waters completely dominate the hydrology.

|

Maps of three typical impounded karsts. Each is a narrow belt of steeply dipping limestone.

Jenolan would count as "Stripe Karst" as it has a L/W ratio of about 25.

impound-1.png

|

Hydrology

As a result of the narrow outcrops, most of the water input is allogenic: derived from adjoining non-limestone areas. These external streams typically sink into the limestone shortly after entering it to form blind valleys and streamsinks, and because they are aggressive they can dissolve large cavities and conduits. Some dry or intermittent valleys may continue across the limestone, possibly passing through arches and gorges. Thus most of the impounded karsts are "fluviokarst".

Generally speaking, water flow in these impounded karsts is dominantly through conduits with some bedding or joint influence. Active vadose passages tend to modify earlier phreatic systems. Storage is limited by the small size of the area, so springs tend to be flashy - although less so than non-karstic streams. The underground plumbing is variable and of limited extent in the smallest areas, but can be quite complex in the larger areas, e.g. Mole Creek, Jenolan, Wombeyan.

Outflow is from springs at the lowest point in the surrounding topography - the groundwater is essentially dammed within the limestone by the surrounding impermeable rocks.

|

Structure, allogenic inputs and internal drainage in a typical impounded karst.

impound-2.png

|

There are exceptions to this general scenario, especially where shallow dips produce more extensive areas of limestone, as at Mole Creek, Tasmania, where more than 200 caves occur in a limestone area about 20 kilometres long by 10 kilometres wide (Jennings, 1967; Kiernan, 1990). There we find a more typical (and complex) karst drainage.

Uplift

Another distinctive feature in the east Australian karsts is the influence of recent uplift. This has produced a strong relief, with deep gorges and knick points both within the karsts and in adjoining valleys, and progressive drops in the base level have left multiple levels of caves, sometimes with entrances to old stream passages hanging in the cliffed gorge walls. See the Buchan example described below.

|

Yarrangobilly Gorge, with the entrance to an abandoned stream cave perched high in the cliff.

S770209.jpg

|

Victoria

In Victoria, the largest impounded karst is at Buchan, where karst development shows a close relationship to the history of surface denudation. The higher level caves are phreatic mazes that formed when the rivers and watertables were 200 metres above the present level nearly 40 million years ago (see interpretive signs). As the valleys deepened, the original caves were drained and deep vadose shafts and fissures developed as the water table dropped. Younger caves occur at lower levels, near that of the present river, and are phreatic systems strongly modified by vadose incision. Flat ceilings indicate old watertables which correlate with river terraces in the adjoining valley. The lowest of these cave levels, only a few meters above the river, contains materials that formed over 750,000 years ago, indicating the great antiquity of the karst as a whole. See White & Grimes, 2007 (ACKMA Field Guide).

The Tropics

In the tropics, surface topography tends to be positive (e.g. Chillagoe) where chemical weathering effects non-limestones as much or more than the limestones, and the rapid development of underground drainage limits the action of surface erosion on the limestones compared to the surrounding rocks. In the temperate climates of NSW and further south chemical weathering of the non-limestones is less important, so the limestones tend to be recessive - forming valleys and basins surrounded by higher hills of non-limestone rocks.

Because the limestones of the tropical impounded karsts stand above the surrounding rocks allogenic drainage is much less important and stream caves are rare. On the other hand vertical rainwater inflow shafts are common.

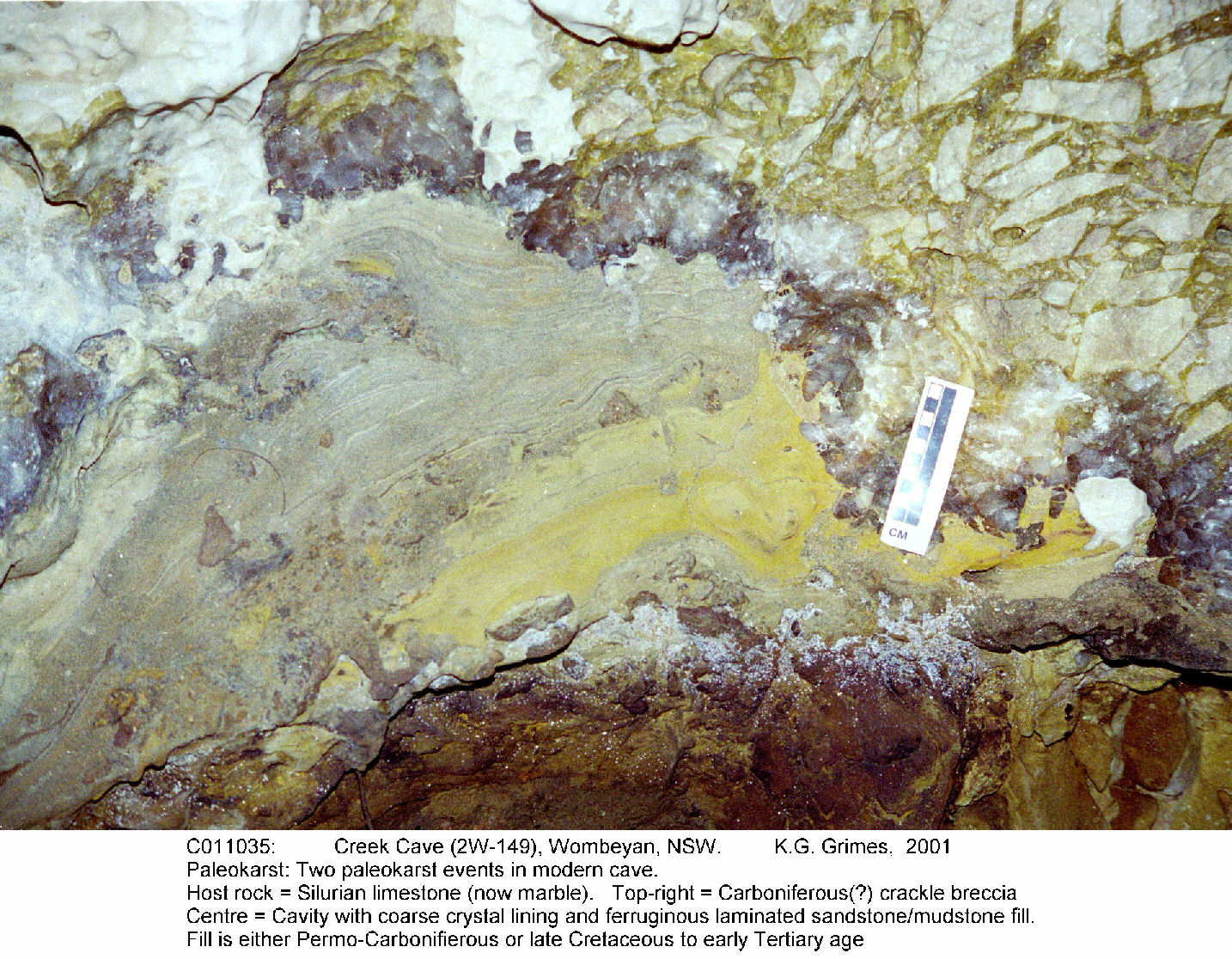

Paleokarsts

Many of the karsts contain paleokarst sequences, often of multiple ages and extending back into the Palaeozoic. e.g. see Osborne (1993).

|

Multi-generation paleokarst at Wombeyan.

1: The host rock is a Silurian marble.

2: The oldest paleokarst, at top right, is a crackle breccia of possible Carboniferous age.

3: That has been cut by a later cavity with coarse sparry lining and a laminated sediment fill of uncertain age - possibly Permo-carboniferous, late Cretaceous or early Tertiary (Osborne, 1993).

4: The present cave cuts all.

Creek Cave, Wombeyan, NSW. 10 cm scale bar

C011035.JPG

|

Jennings, J.N., 1967: Some karst areas of Australia. in JENNINGS, J.N., & MABBUTT, J.A., [eds] Landform Studies from Australia and New Guinea. Australian National University Press, Canberra. 256-292.

Jennings, J.N., 1977: Caves around Canberra. in SPATE, A.P., BRUSH, J., & COGGAN, M., [eds] Proceedings of the Eleventh Biennial Conference, Canberra. Australian Speleological Federation, Canberra. 79-95.

Kiernan, K., 1990: Underground drainage at Mole Creek, Tasmania. Australian Geographical Studies. 28(2): 224-239.

Lauritzen, S-E, 2001: Marble stripe karst of the Scandinavian Caledonides: an end-member in the contact karst spectrum. Acta carsologica, 30(2): 47-79.

Osborne, R.A.L., & Branagan, D.F., 1988: Karst landscapes of New South Wales, Australia. Earth-science Reviews, 25: 467-480.

Osborne, R.A.L. 1993: The history of karstification at Wombeyan Caves, New South Wales, Australia, as revealed by palaeokarst deposits. Cave Science, 20(1): 1-8.

Osborne, R.A.L., 2001: Halls and narrows: network caves in dipping limestone, examples from eastern Australia. Cave and Karst Science, 28: 3-14.

Webb, J.A., Grimes, K.G., & Osborne, R.A.L., 2003: Black Holes: Caves in the Australian Landscape. in Finlayson, B. & Hamilton-Smith, E. (eds.) Beneath the Surface: A Natural History of Australian Caves. Sydney: UNSW Press. pp. 1-52.

White, S. Q., & Grimes, K. G., 2007: Field Guide to the Buchan Karst. Australasian Cave & Karst Management Association, Carlton South. 24 pp.

Selected photographs and diagrams

To view full size images, click on the displayed image.

|

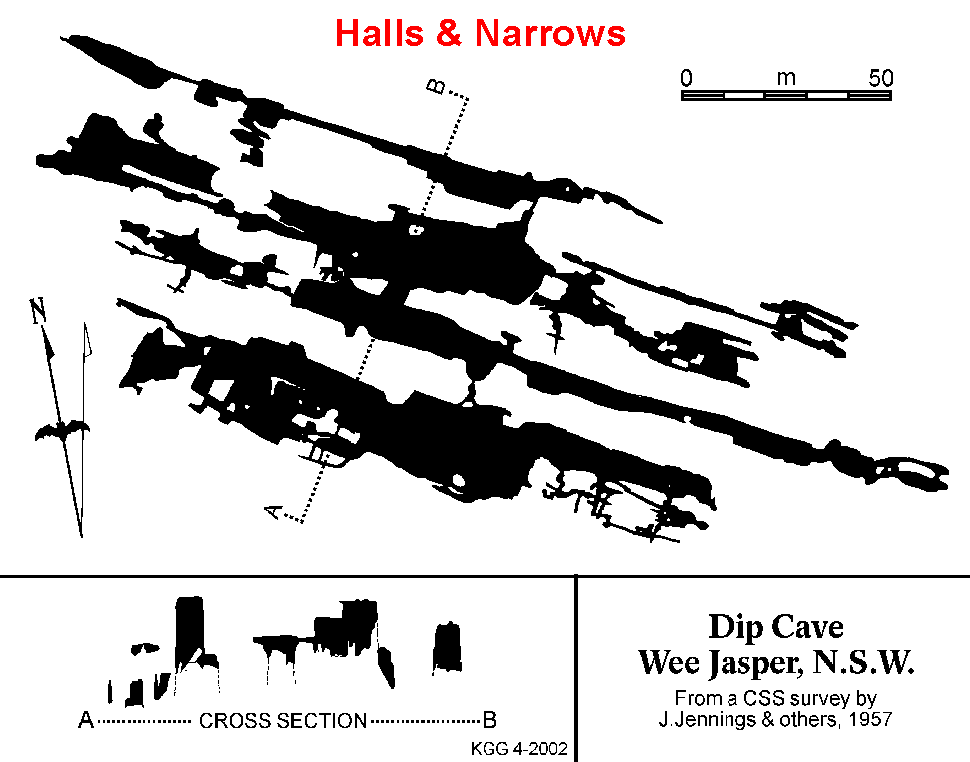

Phreatic systems in steeply dipping limestones can show a "Halls and Narrows" pattern (Osborne, 2001) in which the more soluble beds form large halls with abrupt endings that are joined by small cross-passages (the Narrows) through less-soluble beds.

This example is from Wee Jasper, NSW.

2WJ-halls.png

|

|

Arches are common where allogenic streams have cut through narrow, steep-dipping beds of limestone.

Note the lumpy stalactites, these are organically-influenced "biothems".

Carlotta Arch, Jenolan, NSW

C010113.JPG

|

|

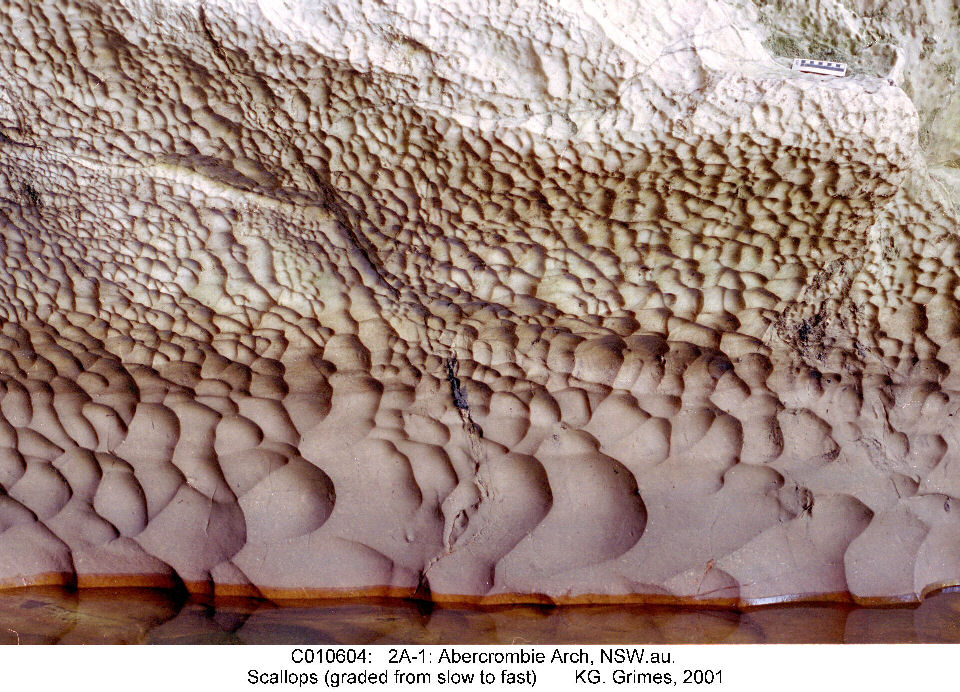

Scallops from stream flows are common. This example from Abercrombie Arch, NSW, shows large (slow) baseflow scallops at the bottom, with smaller, fast-flow patterns formed higher up by flood waters.

10 cm scale bar at top right

C010604.jpg

|

|

A typical keyhole passage, with scallops, formed by stream incision. Grants Cave, Wombeyan NSW.

D052399a.JPG

|

|

paragenetic sculpturing patterns formed in a sediment-filled cavity where water was moving along the sediment-limestone contact and dissolving channels into the limestone. Later removal of the sediments exposed the structures.

FigTree Cave, Wombeyan, NSW.

D030101.jpg

|

|

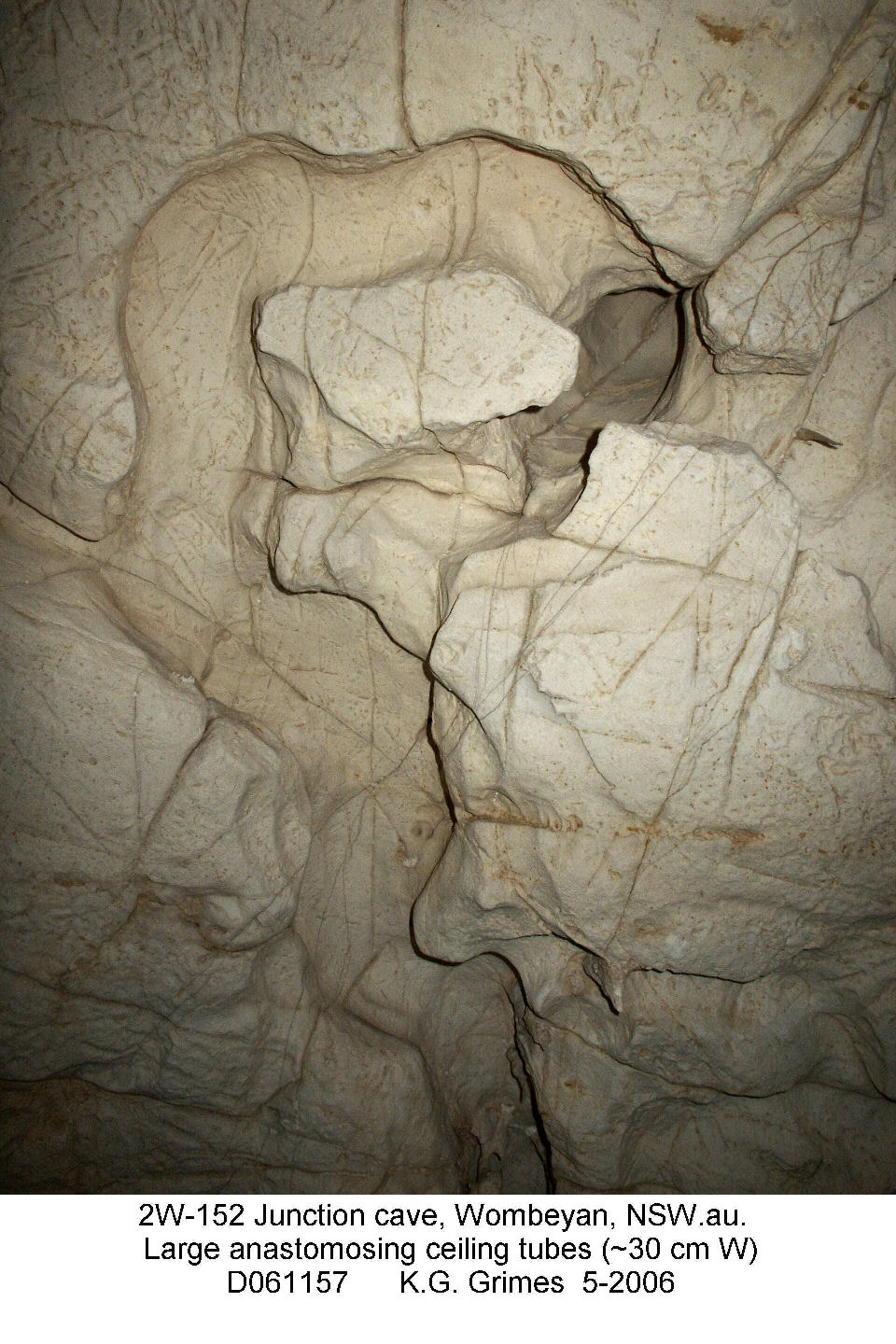

This roof channel (about 30 cm wide) may also have formed paragenetically, when water was forced up against the ceiling, or it may be an early phreatic tube following an inception horizon.

Junction Cave, Wombeyan, NSW.

D061157.JPG

|

|

Side views of two slots with what appear to be anastomosing half-tubes.

Are these left from the early phreatic preparation of the system?

Or are they the result of modern aggressive allogenic flood waters being forced into cracks beside a stream passage?

Victoria Arch, Wombeyan, NSW.

sld091.jpg

|

|

Calcite rafts left after the drying of a cave pool during extreme drought (2005)

FigTree streamway, Wombeyan Caves, NSW.

10 cm scale-bar

D052362.JPG

|

[Top]

[Home] Go to Main Index menu