Kawamoto et al (2004) demonstrated (in a laboratory experiment) a relationship between fingering and initial water content of the sand and the rainfall intensity. Fingers were best developed and narrowest in dry sand and broadened as the initial water content increased to eventually merge into a broad wetting front. Higher rainfall intensity also broadened and merged the fingers. [This relationship to initial water content had also been observed by several earlier workers, eg Dekker & Ritsema 1994 [check?], Bauters et al 2000, Liu et al 1994, ....]

De Rooij (2000) also noted that "A phenomenon related to wetting front instability is the flow over inclined soil layers of contrasting texture, termed funnel flow by Kung (1990a,b). If the groundwater level is sufficiently deep these layers can concentrate the flow of large areas (tens of square metres) in a few finger-like preferential flow paths". Dune dune cross-beds might provide this sort of focussing?

Doerr et al (2000) provide a useful review of "soil repellency" & "hydrophobic" soils. See p.52 for discussion of the resultant focussed flow (he calls it "preferential flow").

........................

Fingers may become permanent once formed, with a persistence up to ....? days. Instability-driven fingers may, in time, become heterogeneity-driven fingers due to leaching processes or internal erosion (Tammo et al, 1996). That last effect will be of importance when we consider the focussed cementation or dissolution of carbonate sands (or other lithologies) by fingered flow.

Focussed solution & cementation

Vertical finger flow through carbonates and other material can produce either solutional pipes or cemented pillars and pinnacles depending on whether the water is undersaturated and aggressive, or oversaturated and likely to precipitate cement in the matrix. Solutional features tend to be self-perpetuating as they enhance the local permeability. Cementation features are however self-inhibiting and this may explain their less-common ocurrance.

Focussed cementation:

If the focused water flow is saturated with carbonate, rather than aggressive, it is saturated and so cemented the sand in vertical cylindrical patterns. The source of the saturated water would be the topsoil of the dune, or possibly younger dune sands which buried the initial dune. The latter situation could explain the earlier generation of solution pipes exposed within the pinnacles at Nambung. Alternatively, the change from unsaturated water that produced the earlier generation of pipes, to saturated water flow might reflect a climate change.Supporting evidence of this process is given by some calcrete hard-pans which have bulbous cemented pendants descending from them into the softer sand below (see photos of caprocks). These inverted pinnacles could result from focussed cementation. Similar pendants and pillars of cemented sand occur in some dune calcarenite caves (e.g. Grimes, 2011)

The focussed cementation process differs from that of the solution pipes in that the pipes are self-perpetuating and can drill down to great depths, whereas the vertical cemented zones would reduce the permeability and deflect the flow to the adjoining less-cemented (ie more-porous) sand unless this tendency is countered by some other factor such as water-repellant (hydrophobic) areas. Thus the cemented area is likely to spread horizontally and eventually cement the whole dune. Perhaps pinnacles are less common than pipes because we only see them where the cementation is incomplete.

The cemented structures become visible after erosion of the less-cemented surrounding material.

Examples from different settings

Geomorphic examples of localised solution and cementation by focussed vadose flow are seen in a variety of situations:

* Sand speleothems:

Pendants, columns or smaller "sand pots", occur within sandy cave fills as a result of either focussed seepage of water from the porous host calcarenite, or by dripping of saturated waters onto sandy floors (Grimes 1998).Taborosi et al (2006, in prep) describe similar pendants of cemented beach sand in sea caves in an island karst situation, and call them "beachrock pendants".

* Syngenetic karst features:

Syngenetic karsts show a range of solution pipes (with and without cemented rims), epikarst pinnacles, cave pendants and cave pillars in dune and beach (& marine) calcarenites. See photos on the pages on "Pipes", "Pinnacles", and caprocks" (the last shows pendant lobes and pillars beneath the calcrete cap). See also Grimes (2004, solution pipes), (2009, pipes and pinnacles), (2011, cemented pendants and pillars); Lipar (2009, pinnacles).

|

|

Calcrete caprock with cemented pipes and pendants beneath it. Dune limestone, on Rottnest Island, WA. KG100945.JPG |

* Laterite Karst:

There are analogies with laterite karsts, where both pinnacles and solution pipes occur - also apparently by focussed cementation and solution, respectively. A significant number of laterite pinnacles are hollow, which suggests cementation adjacent to a pipe.Pendant lobes are seen at base of Fe, Si, Al & Phosphate duricrusts, and pendants and pillars ocur in laterite caves. Polygonal walls occur in lateritic deep weathering profiles, apparently as a result of partial coalescence of expanding pipes. Similar walls were reported by Lipar (2009) connecting the bases of the pinnacles at Nambung.

See Grimes & Spate, 2008; Grimes 2009(poster); Grimes, in press).

For some photos, see Laterite karst page.

* Phosphate hardpans:

Cemented pendant lobes have been reported at the base of phosphate hard-pans on oceanic islands (Stoddart & Scoffin, 1983, p.380).

* Quartz sand dunes:

Pipes and small pinnacles occur in giant podsols in quartz sand dunes. Thompson (1992) described giant podsols in quartzose dune sands of the east coast of Queensland that had irregular pipes of bleached white A2 sand extending as much as 10 m down into the underlying darker Bh horizon, and having widths varying from 1 m down to 1 cm. The pipes had a sharp edge against a thin black organic/humic-cemented rim that graded out to the brighter coloured B horizon material. Less common are small pinnacles of the firmer humic-cemented sand of the Bh, left after erosion of the surounding softer pale sand.

* Vertical pillars in quartz sandstones and quartzites.

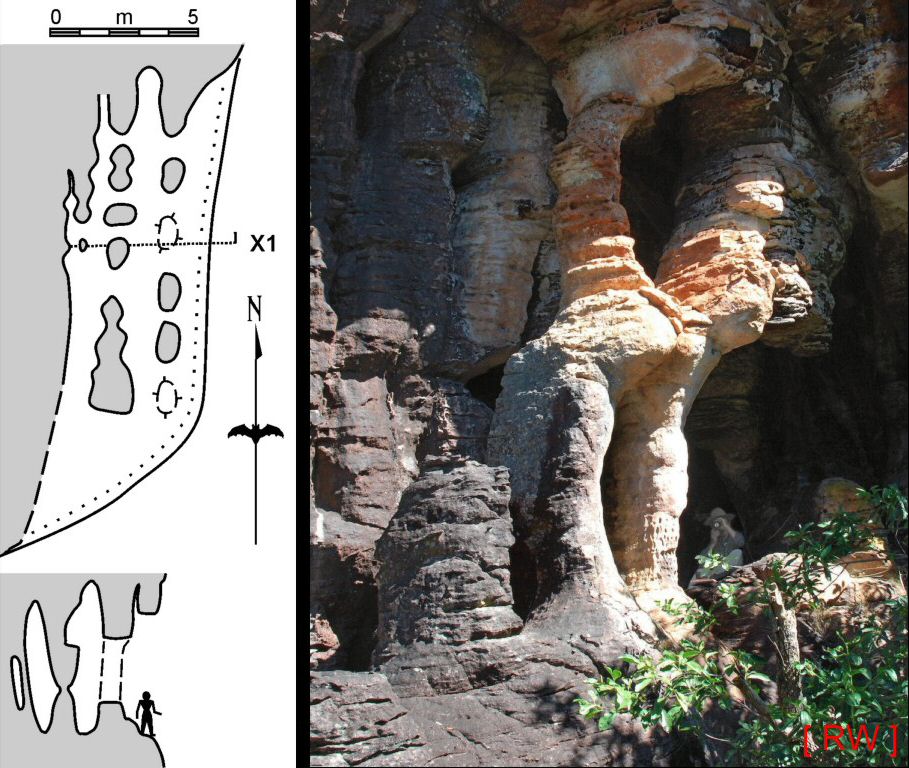

Aubrecht et al 2008, and Grimes et al, 2009a and other workers have shown photos of pillars in the sandstone caves of South America and north Australia (e.g. page 2 in the NSS News of July 2010). Small pillars and pinnacles seen in cliffs and other outcrops at Kakadu are related, but thelarger pinnacles and stoen city blocks are ruiniform features formed by structurally-controlled erosion of jointed sandstones (Grimes et al, 2009a,b ).

|

Pillars associated with a specific bed within a Quartzite cave in Venezuela Photo by M. Audry (see NSS News, July 2010, page 2) |

|

Two levels of sandstone pillars in a cave at Kakadu, NT Photo by Rob Wray. |

* Horizontal tubes in sandstone:

Wray, 2009, Describes horizontal pipes & tubes in Jurassic quartz sandstones of central Quensland which appear to have formed by focussed arenisation followed by piping of the loose sand. The cause of the focussing is uncertain. See also examples in Grimes et al. 2009a|

|

|

Horizontal solution tube through Jurassic sandstone. Mt. Moffatt, Qld. Stereopair - view cross-eyed KG084408a.JPG, KG084407a.JPG |

|

|

Horizontal solution tube, with cemented rim and loose sand on floor. Mt. Moffatt, Qld. KG084663.JPG |

Focussed flow from below - "hypogene" pipes

Similarity in form is not everything, and the following example indicates that some caution needs to be used in interpreting pipes and pillars.In the Pobitite Kamani area of Bulgaria, just west of the Black Sea, there are cemented sandstone pillars/columns and hollow pipes that look very like those found in dune calcarenites. These are formed in an Eocene marine feldspathic-sublabile quartz sandstone and have a calcite cement and have been exposed by erosion of the less-cemented surrounding sand. One of the early explanations of these was that of focussed downward vadose flow that introduced carbonate from an overlying limestone bed (Tchoumatchenco et al, 2007). However, more recently De Boever et al (2008, 2009) have found that the C13 and O18 isotope signatures in the calcite cement support a source from focussed methane seepages rising from below through the soft sands while they were on the sea bed.

They say subsequent meteoric waters followed the initial porous pipes, which might partly explain the visual similarity to solution pipes in calcarenites.

Similar cemented structures (and other less-similar ones) related to the plumbing of cold methane seeps through soft sediments have been described from New Zealand (Nyman et al, 2006). The NZ pipes have thicker cemented rims and thinner central tubes than typical solution pipes in calcarenite.

|

Cemented pipes in the Pobitite Kamani area of Bulgaria. Photo (BeloslavQ.edb_fig01.jpg) from a web site. |

Further Reading

De Boever, E., Dimitrov, L., Muchez1, P., Swennen, R., 2008: The Pobiti Kamani area (Varna, NE Bulgaria) — study of a well-preserved paleo-seep system. Review of the Bulgarian Geological Society, 69 (1-3): 61—68[online at: http://www.bgd.bg/REVIEW_BGS/REVIEW_BGD_2008/PDF/08_De_Boever.pdf]

Dekker, L.W. and Ritsema, C.J., 1994: Fingered flow: The creator of sand columns in dune and beach sands. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 19: 153-164.

Doerr, SH., Shakesby, RA & Walsh, RPD., 2000: Soil water repellency: its causes, characteristics and hydro-geomorphological significance. Earth-Science Reviews 51: 33–65.

Grimes, KG., 2011: Sand structures cemented by focussed flow in dune limestone, Western Australia, Helictite, 40(2): 51-54.

Grimes, KG., 2009: Solution Pipes and Pinnacles in Syngenetic Karst. in: Gines, A., Knez, M. Slabe, T., & Dreybrodt, W. [eds.], Karst Rock Features, Karren Sculpturing, Založba ZRC, Ljubljana.

Lipar, M., 2009: Pinnacle syngenetic karst in Nambung National Park, Western Australia. Acta Carsologica 38(1): 41-50:

Available online at http//carsologica.zrc-sazu.si/downloads/381/4Lipar.pdf. (700 kb)

Nyman, S.L., Nelson, C.S., Campbell, K.A., Schellenberg, F.1,, Pearson, M.J., Kamp, P.J.J., Browne, G.H., and King, P.R. 2006: Tubular carbonate concretions as hydrocarbon migration pathways? Examples from North Island, New Zealand. 2006 New Zealand Petroleum Conference Proceedings, poster paper 21. [online at: http://www.crownminerals.govt.nz/cms/pdf-library/petroleum-conferences-1/2006/papers/Poster_papers_21.pdf

Stoddart, DR., & Scoffin, TP., 1983: Phosphate rock on coral reef islands. in Goudie, AS & Pye, K., (eds) Cemical Sediments and Geomorphology, Academic Press, London. pp. 369-400.

Tammo, SS., Ritsema, CJ., & Dekker, LW., 1996: Introduction. Geoderma 70: 83-85.

(introduction to a special issue of Geoderma dealing with finger flow).

Thompson, C., 1992: Genesis of Podzols on Coastal Dunes in Southern Queensland. I. Field Relationships and Profile Morphology. Aust. J. Soil Res., 30: 593-613

Go to Main Index menu