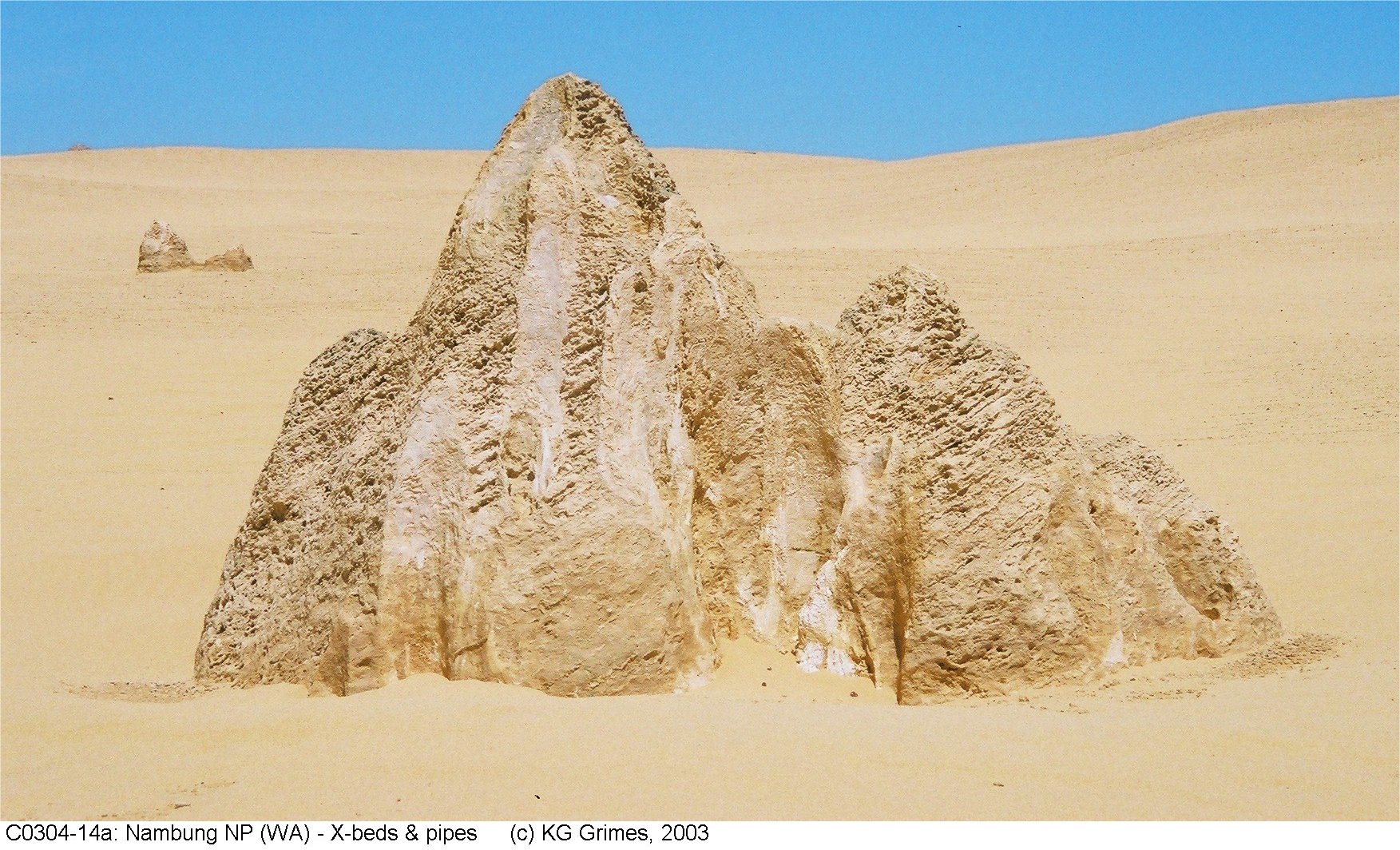

C0304-14.jpg

The Pinnacles at Nambung National Park, and other parts of the coastal dune limestone in Western Australia, might be an extreme case resulting from the coalescence of closely spaced solution pipes in a calcrete band (Lowry, 1973; McNamara, 1995), but they might also involve focussed cementation.

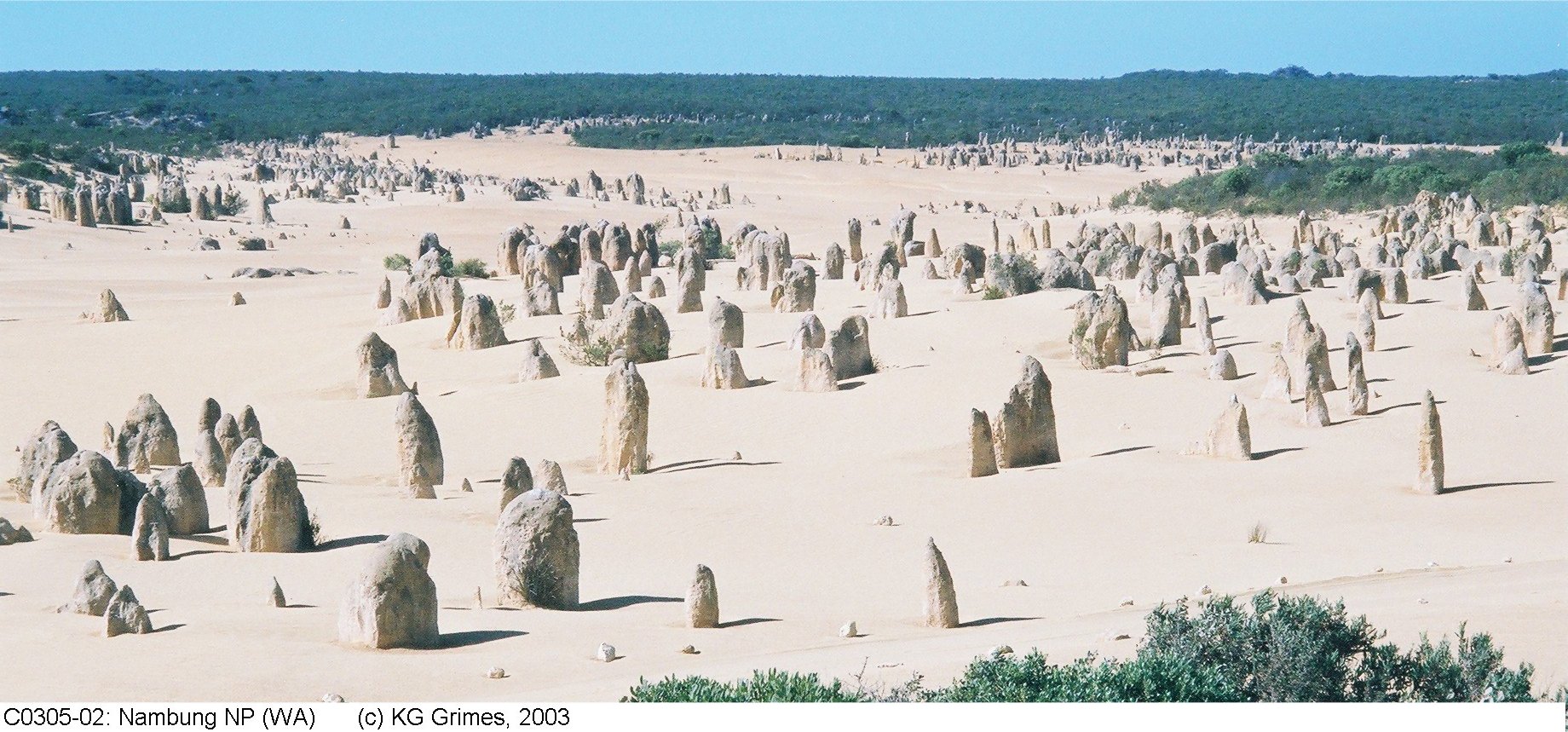

They are exposed in a series of blowouts within a vegetated Pleistocene calcareous dunefield. Obviously they were originally buried by, or formed within, the dune sands.

They are generally discrete pinnacles that are either conical, or cylindrical with a round top. A few are hollow. They are up to 3 m high and 0.5 to 3 m wide. The broader pinnacles are composite structures with multiple peaks. Some irregular forms also occur.

The conical pinnacles are commonly the dissected remnants of a cemented band. The upper part of this band is a hard pedogenic calcrete in which the primary depositional structures have been destroyed, but it grades down into a cemented dune sand where the dune bedding is still visible. At the base cemented rhizomorphs extend downward into the soft parent sand. The tops of the pinnacles show a summit conformity which would be the sharp upper surface of the original calcrete band. Where exposed, their bases may end abruptly or, more usually, grade downward into less-cemented material characterised by abundant rhizomorphs.

The conical and composite pinacles are developed in less-strongly cemented dune sand and have rougher surfaces that show the dune bedding.

Those pinnacles developed in the calcrete have smooth surfaces, but those developed below have rough surfaces resulting from the fretting of the dune bedding and rhizomorphs. Where both types occur together the calcrete may form a phallic bulb at the top of the pinnacle. Sections of an earlier generation of small solution pipes (0.1 to 0.4 m wide) with a hard concentric fill are exposed in both the calcrete and the bedded material. A few pinnacles are formed entirely of cemented pipe fill (Lipar, 2009, figure 5).

Coalescing pipes: The initial view was that pinnacles at Nambung are residual features resulting from coalescence of densely spaced solution pipes that dissected a cemented calcrete band (Lowry, 1973; McNamara, 1995). This view is supported by the occassional occurence of low polygonal ridges connecting the bases of the pinnacles, as shown in figure 4 of Lipar (2009). The hollows between these ridges could be interpreted as large pipes. The genesis is complicated by the presence of an earlier generation of solution pipes, with cemented concentric-banded fill, that is exposed in the sides of the later pinnacles.

Lowry (1973) suggested the following stages in development of the Nambung Pinnacles:

McNamara (1995) extended Lowry's model to suggest that some of the more cylindrical pinnacles might have formed by cementation around tap roots in zones up to 1 m wide. He also noted that some of the small pinnacles could be the cemented fill of prior solution pipes, as illustrated by Lipar (2009, figure 5).

Focussed cementation: The focussing of the water could occur in several ways, as suggested for solution pipes (Grimes, 2009), but in this case instead of the water being aggressive, it is saturated and so cemented the sand in vertical cylindrical patterns. The source of the saturated water would be the topsoil of the dune, or possibly younger dune sands which buried the initial dune. The latter situation could explain the earlier generation of solution pipes exposed within the pinnacles at Nambung. Alternatively, the change from unsaturated water that produced the earlier generation of pipes, to saturated water flow might reflect a climate change.

Supporting evidence of this process is given by some calcrete hard-pans which have bulbous cemented pendants descending from them into the softer sand below (see photos of caprocks). These inverted pinnacles could result from focussed cementation. Similar pendants and pillars of cemented sand occur in some dune calcarenite caves (e.g. Grimes, 2011)

The focussed cementation process differs from that of the solution pipes in that the pipes are self-perpetuating and can drill down to great depths, whereas the vertical cemented zones would reduce the permeability and deflect the flow so that the cemented area spreads horizontally and eventually cements the whole dune. Perhaps pinnacles are less common than pipes because we only see them where the cementation is incomplete.

A polygenetic view: Both of the suggested processes, coalescing solution pipes and focussed cementation, could be valid. The cylindrical pinnacles might have formed by focussed cementation, as would the hollow pinnacles which would be due to cementation around a solution pipe. However, the composite, conical, and irregular pinnacles might be the result of coalescing pipes. A few pinnacles seem to be the cemented cores of solution pipes.

Lipar (2009) provides additional field data and also suggests a polygenetic origin for the pinnacles, with roots playing a major role.

Grimes, KG., 2009: Solution Pipes and Pinnacles in Syngenetic Karst. in: Gines, A., Knez, M. Slabe, T., & Dreybrodt, W. [eds.], Karst Rock Features, Karren Sculpturing, Založba ZRC, Ljubljana.

Lipar, M., 2009: Pinnacle syngenetic karst in Nambung National Park, Western Australia. Acta Carsologica 38(1): 41-50:

Available online at http//carsologica.zrc-sazu.si/downloads/381/4Lipar.pdf. (700 kb)

Lowry, D.C., 1973: Origin of the Pinnacles. Australian Speleological Federation Newsletter. 62: 7-8.

McNamara, K.J., 1995: Pinnacles [revised edition], Western Australian Museum, Perth. 24 pp.

|

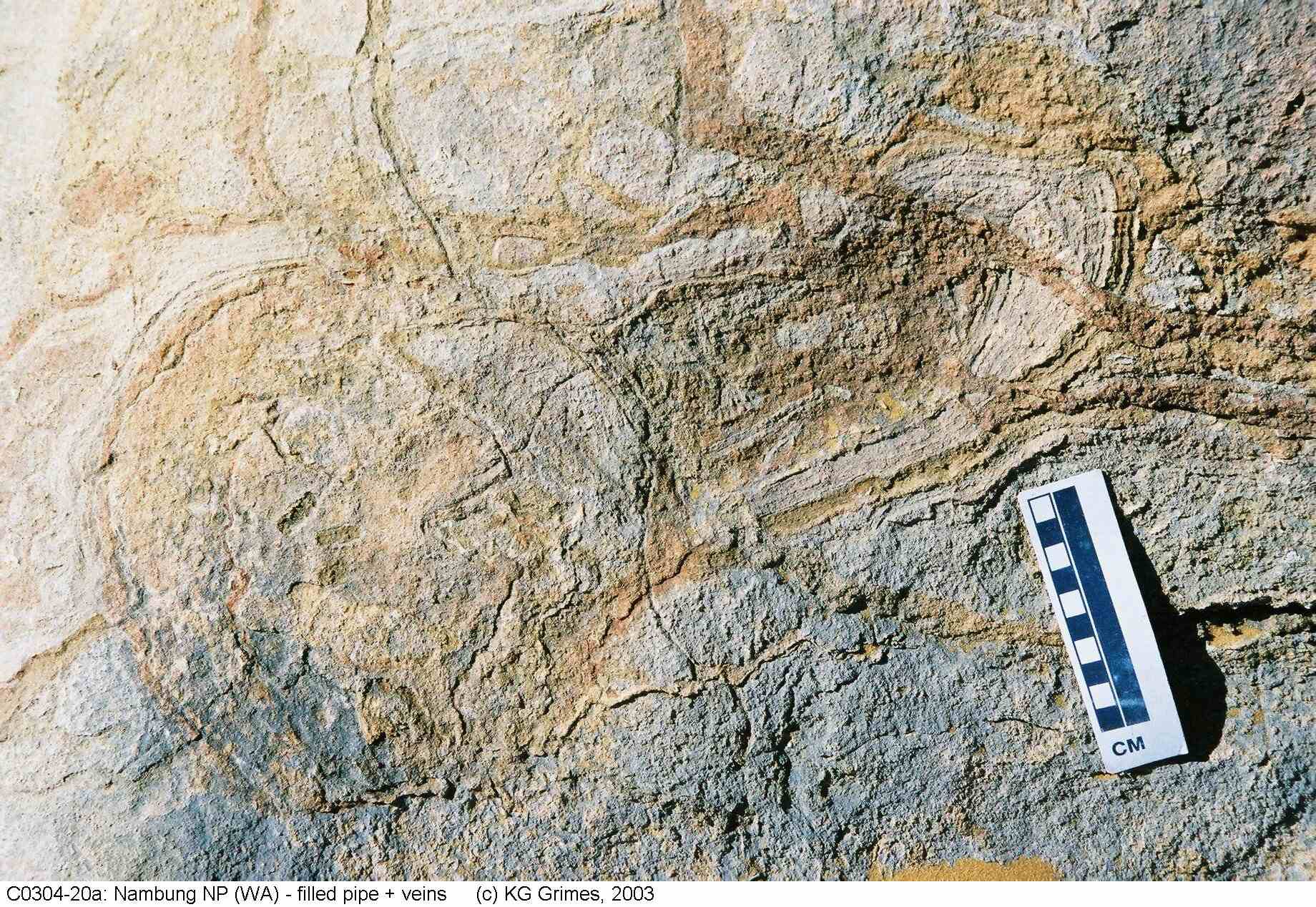

Detail of bedded dune limestone cut by small filled pipes. Exposed in the side of a pinnacle. 10 cm scale bar. C0305-12.jpg |

|

A group of round-topped, cylindrical pinnacles. These are developed in the hard calcrete at the top of the indurated band. IMG00213.jpg |

|

A hollow pinnacle. A small percentage (~1% ?) of the pinnacles are hollow. Possibly these are solution pipes, with thick cemented rims and softer cores, that relate to the earlier stage when the hard pan and calcrete was formed? Similar hollow pinnacles occur in Laterite Karsts. 10 cm scale bar at base. C0304-17.jpg |

|

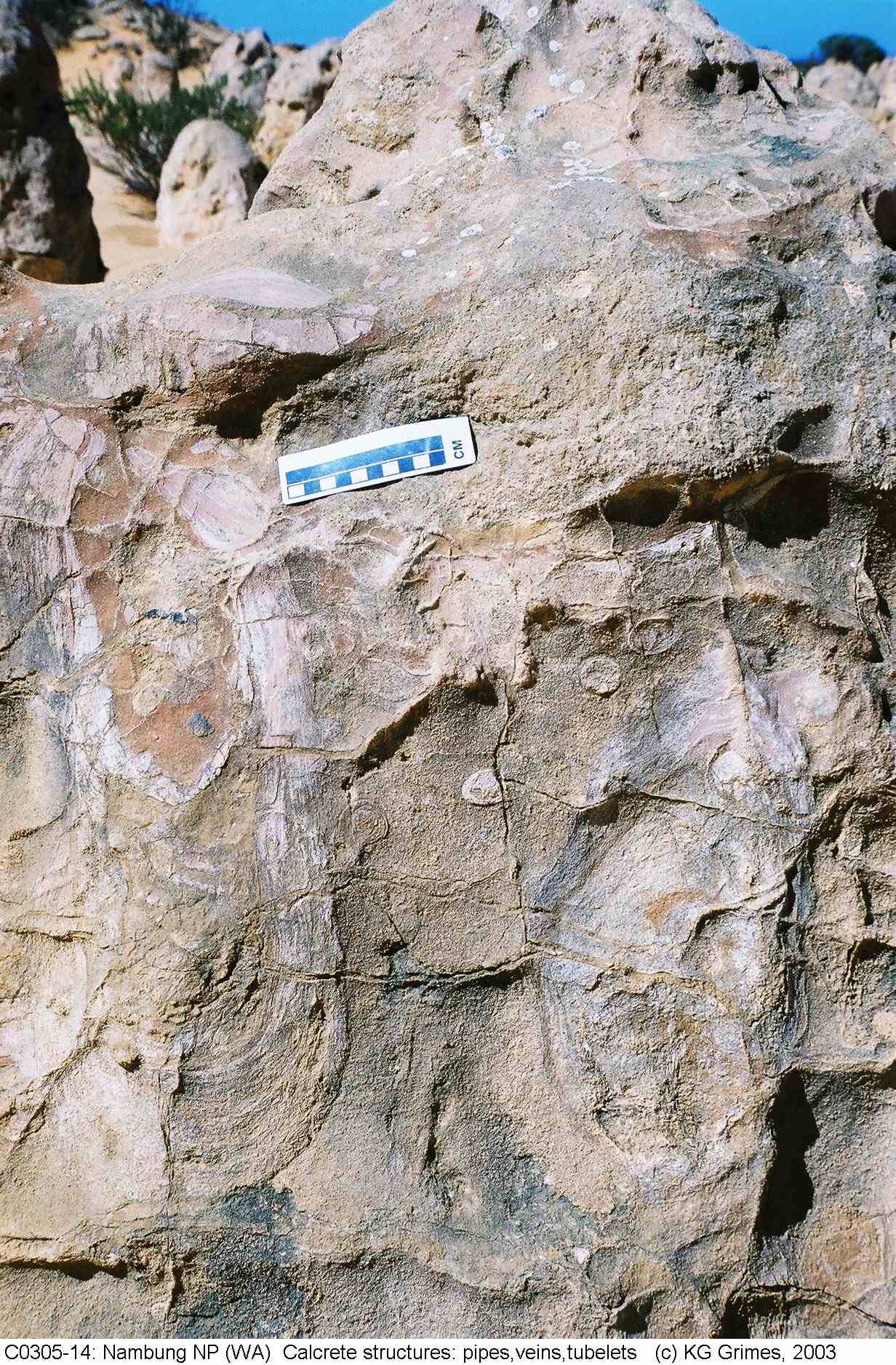

Calcrete structures exposed in the side of a pinnacle. C0305-15.jpg |

|

Calcrete structures exposed in the side of a pinnacle: A filled pipe (concentric structures) is cut by later veins. C0304-20.jpg |

|

Calcrete structures exposed in the side of a pinnacle: Assorted pipes, veins and tubelets C0305-14.jpg |